When Susan Galbraith joined AstraZeneca back in 2010, the company was enduring one of big pharma’s longest-running and worst R&D losing streaks ever, with at least six late-stage failures over a seven-year period.

This saw phase 3 flops of drugs for stroke, prostate cancer and depression – failures that dented confidence in the firm as patent expiries for its blockbusters Crestor and Nexium loomed on the horizon.

But in retrospect, 2010 was a turning point for the company. This began when Mene Pangalos was hired to head AstraZeneca’s Innovative Medicines and Early Development (IMED) Biotech Unit, and introduce a more rational and hardheaded approach to drug development.

Pangalos swiftly recruited oncologist Susan Galbraith, then working at Bristol- Myers Squibb, to head AstraZeneca’s IMED oncology team, which focused on small molecule drug development in oncology.

Eight years on, three new oncology drugs are proving to be the driving force for the new AstraZeneca: small molecule, targeted lung cancer drug Tagrisso (osimertinib) and ovarian cancer treatment Lynparza (olaparib) plus biologic PD-L1 immunotherapy Imfinzi (durvalumab).

EvaluatePharma forecasts that Lynparza (now co-marketed with Merck & Co) will hit annual revenues of $2.2bn by 2024, with Imfinzi expected to reach $3.65bn and Tagrisso leading the way with sales just shy of $4bn.

Imfinzi, competing in the hypercompetitive world of immuno-oncology, was developed by MedImmune, the company’s US-based biologics research division, while the two small molecule drugs were developed in the UK by Galbraith’s IMED oncology team.

The clinical and commercial success of these three cancer therapies has helped restore self-belief among AstraZeneca employees, and will help make 2019 the year the company returns to top-line revenue growth after years of patent-expiry-induced decline. So how did AstraZeneca achieve this turnaround? In 2010 Mene Pangalos introduced a ‘5R framework’ for R&D: right target, right patient, right tissue, right safety, right commercial potential.

A study published earlier this year found that the proportion of pipeline molecules at the unit that moved from preclinical investigation to completion of phase 3 trials rose from 4% to 19% between 2012 and 2016. The report compares this with an industry average of 6%, as cited in CMR International’s 2016 Global R&D Performance Metrics Programme.

When Pharma Market Europe named Susan Galbraith in its list of 30 Women Leaders in UK Healthcare in June this year, Pangalos was quick to credit her role in the renaissance. “Susan was one of the first leaders I hired when I joined AstraZeneca and has been a forceful driver of change across the company over the past eight years,” he told PME.

She is focused on scientific rigour and quality, with a passion for getting things done to ultimately deliver life-changing medicines for cancer patients. She is resilient and one of our most tenacious and inspiring leaders. She has truly had a significant impact on transforming AstraZeneca’s pipeline.”

Galbraith’s unit has not only demonstrated good judgement about picking winning molecules, but has also shown speed: Tagrisso is one of the fastest-ever developed drugs, with AZ taking it from clinical trials to FDA approval in just over two years.

Naturally Galbraith isn’t resting on her laurels, and wants to talk to PME not about past successes, but current and future challenges in oncology.

Four fronts against cancer

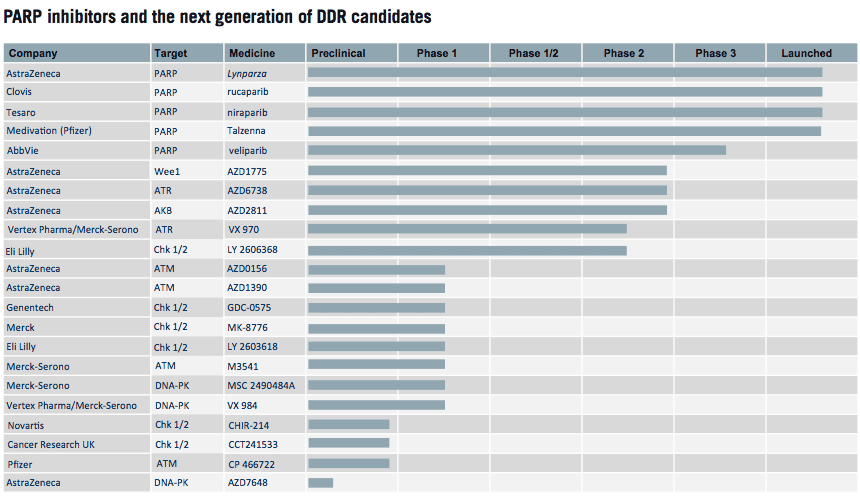

The company is pursuing innovation across four domains in oncology: tumour drivers and resistance mechanisms; DNA Damage Response (DDR) with PARP inhibitor Lynparza leading the way in this category, with other new mechanisms now in the pipeline.

The third area is immuno-oncology (IO) which spans biologic IO led by Jean Charles Soria at MedImmune, while Galbraith is also working on what she calls an “exciting” group of small molecule IO agents.

Finally, there are antibody drug conjugate programmes led out of MedImmune. “If you really want to improve survival outcomes for patients with cancer, you have to treat them earlier,” she says. “These targeted therapies show a great deal of potential if you use them sooner, so we’re focused on what we can do to enable a faster move into earlier stage disease.”

The company has studies of Lynparaza, Imfinzi and Tagrisso in first-line and adjuvant settings, and is also putting these together with other existing and novel agents, as part of the industry-wide race to find the most effective combinations.

Like its peers, AstraZeneca is exploring the use of a range of new technologies to help accelerate this process and improve outcomes. This encompasses approaches to detecting cancers earlier, including novel techniques such as liquid biopsies (aka circulating tumour DNA tests) and new companion diagnostics. AstraZeneca is collaborating with numerous firms in this field, including Foundation Medicine, which specialises in next-generation gene sequencing technology.

Another key development is a rise in prospective lung cancer screening in high- risk patients, with the aim of spotting a tumour far earlier than normal.

The NELSON trial, which looked at screening in Europe, was presented at the recent World Conference on Lung Cancer. It found the use of a CT scan could reduce the risk of lung cancer deaths by 26% at ten years, and even more so in women – something which, if introduced into standard practice, could transform outcomes.

Cambridge’s lead in understanding DNA Damage Response

As its name suggests, DNA Damage Response (DDR) is the body’s own mechanism for responding to damage to DNA, the genetic instructions in each of our cells, damage to which is often the trigger for cells to become cancerous.

AstraZeneca’s lead in DDR goes back to 2005, when it acquired Kudos, the Cambridge (UK)-based company set up by Professor Steve Jackson, a world-leading pioneer in the field.

Steve Jackson is a lead author of a Nature paper which described the sensitivity induced in BRCA mutation tumours due to inhibition of poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), a protein which helps damaged cells to repair themselves.

People who have BRCA gene mutations have an increased risk of certain cancers, including breast cancer, ovarian cancer and prostate cancer. The PARP inhibitor drug prevents BRCA mutation-carrying cells from repairing themselves, causing them to die.

KUDOS had discovered olaparib, the first-in- class PARP inhibitor, which Galbraith’s team developed and brought to market as Lynparza. She says understanding about the role of a host of other DDR pathways and mechanisms is deepening – and AstraZeneca is leading the industry.

“Beyond BRCA mutation, there is another set of abnormalities that is quite common in cancer – actually about 20% of all cancers might have a deficiency in the ability to repair their DNA.”

Beyond Lynparza, AstraZeneca has a number of assets in phase 2 and in early development: a WEE1 inhibitor (adavosertib, AZD1775), an ATR inhibitor (AZD6738), two ATM inhibitors (AZD1390 and AZD0156), and a DNA-PK inhibitor, all of which target different aspects of the DDR, and these could be deployed either in monotherapy, or in combination with standard of care treatments or with Lynparza.

Galbraith says there is also promise in combining DDR with immuno-oncology.

“One of the mechanisms involves abnormalities in DNA repair, which create broken fragments of DNA in the wrong part of the cell. This stimulates an immune response similar to that seen against a viral infection.

“So that’s the rationale behind combinations of DDR agents with immuno-oncology. We’re excited by the potential of the agents we’re exploring now and we’ll see the read-outs over the next few years.”

Of course, AstraZeneca isn’t immune to the setbacks of old – its IO drug Imfinzi is witness to that. On one hand, it has scored a major success this year by gaining US and EU approval as a monotherapy maintenance treatment for NSCLC patients with inoperable stage 3 disease, ie that has not spread widely around the body after platinum chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

This gives it a unique niche in an IO lung cancer market dominated by Merck & Co’s Keytruda, and prevented it from being an also-ran.

However, recent overall survival results from the MYSTIC trial, which studied Imfinzi with CTLA4 inhibitor tremelimumab, have just confirmed the combination failed to outperform chemotherapy in previously untreated stage 4 NSCLC patients with higher levels of PD-L1 expression in their tumours.

There’s no doubt this was a blow – but AstraZeneca has cause to be more optimistic in the DDR field, as it has a significant lead. Equally it will have to be ready for some knock-backs along the way, especially in two-drug oncology combinations, a field which remains highly unpredictable.

Women in science

AstraZeneca has shown its commitment to increasing the number of women on leadership teams; today women make up about half of its global workforce and just over 40% of the Board. Despite progress here and across the industry, Galbraith is still unusual in being a woman leader in drug development. Her high profile and success has led her to become a spokesperson for ensuring more women follow in her footsteps.

“There has been huge progress over the last 20 years in the number of women coming into 30 www.pmlive.com life science degrees and joining biosciences and biochemistry. However we’ve still got a small proportion of women in chemistry and some other roles in the pharmaceutical industry.”

It’s clear that motherhood still has an adverse impact on many women’s careers, preventing them from ever making it into senior roles.

There’s no doubt that employers are attempting to bridge this gender gap by finding ways to support and encourage women’s career advancement when they have children – but there are wider shifts in social attitudes that also need to happen.

“Until you get men taking time off to look after their young kids alongside women, and that becomes normal, that gap will persist,” says Galbraith.

Other key issues include nurturing self- confidence in potential women leaders, and their belief in their own ability to influence at a senior level, whichAZ is supporting through training and mentorship.

“Those are skill sets that can be taught and are being taught,” she says. “Within AstraZeneca we have a ‘Women as Leaders’ course, which I think has been really helpful. There’s a number of these support systems in place, and we’ve seen a substantial increase over the last five years or so in the percentage of women in senior scientific roles.”

Galbraith is concerned about the rise in reported anxiety and mental health problems in young people, with young women most vulnerable.

“I don’t think we know whether things like social media is a contributor but we can do more to talk about the stresses of modern life, and try to equip young people with the tools they need to be more resilient and self confident.

“I think we’re still not maximising the potential of young women who’ve gone through university, to be honest with you. We need to get the best out of the next generation of a bright, committed, hard-working group of women.”

A drive to do more

Returning to the theme of cancer research, Galbraith says there is still much more progress to be made – especially in lung cancer, the biggest cancer killer in both men and women. “We’re starting to see that we can make the same progress in lung cancer that we’ve made in breast cancer. It’s incredibly rewarding to work in this field, and I hope we can translate to make a bigger difference over the next ten years in the outcomes of patients.”