The BRIC nations are developing pharmaceutical markets that are comparable in size to many of their more mature Western counterparts. But in terms of the size of the opportunities for future growth, traditional markets are seemingly being dwarfed by the burgeoning behemoths of Brazil, Russia, India and China.

In fact, such has been the rate of progress that their collective tag as ‘emerging’ nations is undoubtedly out of date. The chrysalis has fallen away and their metamorphosis into markets of global importance is now drawing widespread corporate attention. IMS Health data shows that in 2011 China cemented its place as the third largest pharmaceutical market in the world – almost 50 per cent bigger than Germany in fourth place – while Brazil overtook the UK, Italy, Spain and Canada to take sixth spot. Russia and India enjoyed similarly impressive uplifts.

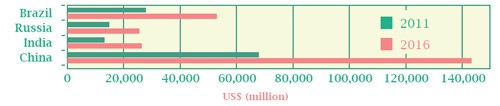

Growth is forecast to continue for the foreseeable future. IMS Health predicts that pharmaceutical sales in China will increase from $65.77bn (2011) to reach $143bn by 2016. Likewise, it also anticipates that total sales in Brazil will almost double from $27.69bn (2011) to $52.94bn in the same period. Sales in Russia are expected to enjoy compound annual growth of 11.5 per cent in the next three years, yielding revenues of $25.4bn by 2016 – while India is tipped to overtake Russia as the third biggest BRIC nation, with revenues doubling from $13bn in 2011 to $26.3bn in 2016.

To set this in context, UK sales in 2011 totaled $21.6bn.

The journey towards giants

The grouping of four diverse nations under one general banner – BRIC – has served a useful purpose for analysts, economists and corporate strategists for many years, but it has also masked the idiosyncrasies and challenges faced by each nation as their evolution has played out. Their individual journeys from emerging markets to major players on the global stage have not followed a template, but have been underpinned by local variations on common challenges.

Infrastructure, reform and reimbursement

The development of infrastructure and health systems that can help improve access to healthcare for local populations has been a recurrent theme across the BRIC nations.

And such development sits at the root of the opportunity for pharmaceutical growth.

But, rather like the rest of the global market, healthcare systems in all of the developing nations have been under sustained pressure to contain cost. Despite the common themes, progress in the BRIC regions has not happened in synchronicity – with the pace and rate of change naturally differing from country to country.

Market size by country: 2011 and 2016

At ex-manufactuer prices

Source: IMS Health

China

In 2009, China introduced a healthcare reform programme to deliver universal coverage and basic, low-cost health services to all of its 1.3bn citizens. In 2006, less than half the population enjoyed health coverage, but the new legislation hoped to increase this to around 90 per cent by the end of 2011. The policy was underpinned by the creation of two insurance programmes for low-income citizens – Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) and the New Rural Cooperative Medical System (NRCMS). Alongside this, citizens working for state-owned or private enterprises would continue to be eligible for Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance – China’s most comprehensive health insurance. Despite the new schemes, healthcare in China is still considered expensive, with out-ofpocket payments commonly high.

Moreover, healthcare resources in China remain unevenly distributed and, in the continued absence of an effective primary care system, patients in rural areas still experience significant difficulties accessing healthcare.

The government has attempted to address this by establishing Community Health Centres (CHCs) in urban areas and small, high-standard hospitals in rural areas. But observers report that, despite the introduction of around 7000 CHCs by 2011, few are new, while many are simply small (Class I and II) hospitals that have been converted and rebranded. Typically, the facilities and doctors’ skills levels at CHCs are considered inferior to expensive Class III hospitals.

In addition to the increases in funding and insurance coverage and the expansion of primary care, the 2009 reforms also marked the introduction of the Essential Drugs Lists (EDL) System. Under the new system, primary health care institutions can only stock and prescribe essential medicines on the list – limiting the number of expensive drugs that can be used at CHCs. Hospitals, on the other hand, enjoy greater latitude. The limited access to high-value brands at primary health institutions has been identified as a further barrier to the government’s aim of shifting patients to CHCs from more expensive secondary care. The EDL was revised in March 2013, with a further 213 new medicines added as essential drugs – coming into force from May 2013.

In fact, the 2009 health reforms focused heavily on policies around pricing and reimbursement, including plans to introduce a ‘scientific medicine pricing mechanism’.

As part of this, China began working with the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 2009 to develop clinical guidelines and inform the Chinese government’s Clinical Pathways project. In the longer-term, it is possible that a ‘China NICE’ could be established, mirroring the UK’s approach to health technology assessment.

Russia

Reform in Russia began in 2005 with the introduction of a state reimbursement programme, which aimed to provide outpatient drug coverage to patients in specific disease groups. The DLO initially offered extended drug coverage to around 10 per cent of the population, with the remainder covered by a health insurance system that provided coverage for inpatient drugs and services only – underpinned by a basic Essential Drugs List. More recently, two reform programmes have been introduced to fill the gaps in the system; Development of Health 2020 and Pharmaceutical 2020.

Development of Health 2020 aims to extend basic healthcare coverage to include the reimbursement of outpatient drugs, and the unification of EDL and DLO lists to form part of a system of universal healthcare coverage. Pilot schemes are being rolled out from 2013, with full implementation expected by 2020. Analysts believe this to be optimistic.

Pharmaceutical 2020 aims to substitute 50 per cent of all generic drugs with domestic alternatives by 2017, and domestically manufacture half of all innovative drugs by 2020. The policy, which received government funding of $4bn in March 2011, has provided a catalyst for major domestic and international investment in the Russian pharma industry.

Further, the inference that locally-produced drugs may gain preferential access to state reimbursement lists has provided an added incentive for international manufacturers to invest in Russian infrastructure. In 2011, The Association of International Pharmaceutical Manufacturers pledged a minimum of $1bn in investment in Russian manufacturing, packaging and R&D. Novartis – which is investing $500m over the course of five years – Nycomed, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi have all developed operations in Russia since 2010. Others, such as Roche, are partnering with local manufacturers under out-licensing agreements.

India

Healthcare spending by federal and state governments in India has increased significantly in the past five years – but targets in key indicators such as infant mortality rates and maternal mortality rates have all been missed. Despite the rapid growth of the Indian economy, critics cite a lack of funding in infrastructure and healthcare personnel as major contributory factors in poor health indicators. In response, the Government has increased health expenditure from 1.4 per cent to 2.5 per cent of GDP by the end of the twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012-2017). During the course of the previous plan, the hospital sector grew considerably, with the addition of 15,000 health sub-centres and 28,000 nurses and midwives in the five years preceding 2012.

The number of primary health centres grew by more than 80 per cent in the same period, reaching more than 20,000 by the middle of last year. But hospitals still account for 50 per cent of India’s healthcare industry – and are likely to represent a key driver of pharma growth in the future.

Improving access to healthcare remains a priority for India’s Ministry of Health – but this is being tackled against a backdrop of cost-containment measures to control the prescribing of high-priced medicines. The government has issued high-profile proposals around compulsory licensing and price-capping. In September 2012, a landmark proposal to cap the maximum price at which essential drugs can be sold was unveiled. This will affect all 349 drugs on the National List of Essential Medicines – around 60 per cent of the domestic market.

Patent protection is also under the microscope, with suggestions that pharma brands could be eliminated from India altogether. While debate around the 2005 Indian Patent Act, which was amended in March 2012, continues to attract pharma’s gaze, recent news does little to encourage optimism. In April 2013, Novartis was denied patent protection for its cancer drug, Glivec, by the Indian Supreme Court. This follows similar patent defeats in India for Pegasys, Roche’s hepatitis drug, Merck’s asthma treatment, Singulair, Gilead’s Viread (HIV) and Pfizer’s Sutent (cancer). Analysts warn that such patent rulings could discourage big pharma investment in India.

Brazil

The healthcare system in Brazil has been steadily evolving since the creation of the Unified Health System (SUS) in 1989 and the subsequent introduction of the Family Health Programme in 1994. The Brazilian constitution guarantees the state provision of high-quality healthcare as a universal right – but as in all developing nations, access – and funding – is uneven, and patients are still subjected to high out-of-pocket payments.

Despite this, the country has made considerable progress against the millennium targets of reductions in child mortality, improving maternal health and fighting AIDS, malaria and other diseases. In the next decade, the Brazilian government aims to take 16 million people out of poverty and ensure they are covered by the healthcare system. PwC predicts that health spending in Brazil will grow by 62 per cent between 2010 and 2020.

The presence of multinational pharmaceutical companies in Brazil has grown in recent years, largely due to an increase in the acquisition of local generics companies. Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi and Amgen are among the high-profile pharma companies to invest in, or partner with, Brazilian generics manufacturers.

While generics account for around a quarter of all medicines sold in Brazil – making it the largest generics market in Latin America – analysts believe there is much room for growth in the sector. Conversely, however, Brazil’s uptake of New Molecular Entities (NMEs) between 2006-2010 was the highest of the BRIC nations – with 34 per cent of global NMEs available in the country. Nevertheless, the 2012 introduction of a new HTA body, CONITEC, to assist the Ministry of Health on Unified Healthcare System (SUS) reimbursement decisions, creates a new barrier to market access in Brazil. CONITEC’s creation followed 2010 consultation with NICE, and provides further evidence of the UK watchdog’s growing international influence on healthcare policy.

This article was originally published in the PME supplement Pharma and BRIC