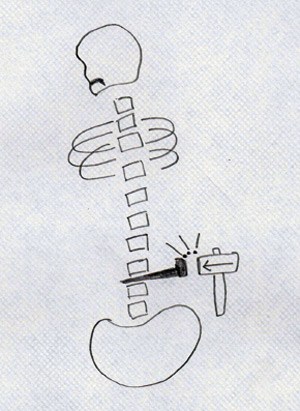

Artistic response to illness, drawn by the patients: Nerve injury in the middle finger

Deep in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in South-West France lie the earliest known human cave paintings. The images (which will be familiar to viewers of Werner Herzog’s 2010 documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams) include breathtaking snapshots of the palaeolithic world, and are thought to be over 30,000 years old. It’s probably impossible to sum up the significance of an archeological jewel like this, but I would like to focus on one key lesson that the Chauvet Cave teaches us: human beings have an instinct to visually depict their world, to say ‘I am here, and this is what I see’.

Flash forward 30 centuries or so and this urge is still going strong. Right now, young children around the globe are drawing and painting pictures of things they’ve seen or imagined, expressing their own view of the world in the process. Unfortunately, many of us stop expressing ourselves like this as we get older (the occasional doodle in a late-afternoon meeting notwithstanding). As a medical filmmaker, I’ve seen that there is much to be gained from reconnecting people with their artistic impulses, and when we encourage adult and adolescent patients in particular to do so we create a deeper and broader dialogue between patients, HCPs and industry.

When engaging with adult patients we often prioritise verbal communication; in interviews, questionnaires, online forums and, indeed, films. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with that – asking questions and listening carefully to patients’ answers is a great way to generate considered, detailed and specific insights into the patient experience. But it’s not without pitfalls.

At a basic level, everyone varies in their degree of linguistic articulacy and some people, however intelligent or perceptive, may struggle to express themselves through the spoken or written word. Furthermore, when dealing with something as sensory, emotional and personal as illness, language can often seem to come up short. Have you ever had a deeply emotional experience and then struggled in vain to explain it to someone else, constantly feeling like you can’t quite find the words to say what you mean? We all have, and I think this gives a sense of what it must be like trying to describe life with a rare or unique illness. This carries two main risks. Firstly, the patients in question might become discouraged, feel that they can’t express what they mean and withdraw from the dialogue. Secondly, patients may simply resort to cliches which, by virtue of their inherently general nature, don’t tell you much about their individual patient journeys.

Artistic response to illness, drawn by the patients: Herniated spinal disc

Ironically, the very strengths of linguistic communication can also be its downfall. To some degree, most of us have learnt to consider our words and think before we engage our mouths (or pens, or keyboards). This will be especially true for patients who are talking to a medical communicator, researcher or industry professional they’ve just met – the atmosphere may be more ‘professional meeting’ than ‘social event’ and the patients are less likely to talk freely than they would with a friend. The result tends to be very rational and mediated responses to questions. But we know illnesses aren’t only experienced rationally, they’re sensory and emotional as well. On top of this, in any sort of question-and-answer environment patients are likely to infer that there are ‘right answers’ to the questions; they may start to self-edit or say what they think the questioner wants to hear rather than what they really feel.

There is ever-growing potential for industry to invite these sorts of pictorial, artistic contributions directly from the patients

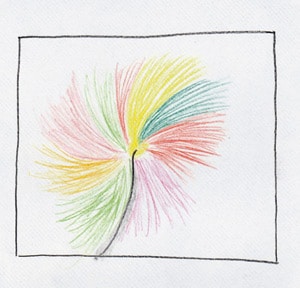

Again, as a language-driven species verbal communication will always be our bread-and-butter route to engaging with patients and seeking out insights. Quite right. But, alongside this, more can be done. Increasingly over the last few years my partners (mainly medical communications and research agencies) and I have been asking patients to keep short art diaries before or after we film with them. The patients are usually given a notepad and some coloured pencils and asked to draw one sketch a day, showing how they feel about their illness at that moment. The sketches can be detailed or sparse, literal or abstract. And the results are frequently stunning, tapping into a well of hidden creativity and expressive potential. I’ve seen all manner of takes on this simple brief, from simple and realistic pictures of physical symptoms, to intricate and surreal cartoons.

As social media platforms become increasingly central to the way the healthcare industry engages with patients, there is ever-growing potential for industry to invite these sorts of pictorial, artistic contributions directly from the patients they’re speaking to. Indeed, as more and more apps are developed to support patients in specific therapy areas (many of which are already diary-based in design), there are even more routes for patients to communicate their experiences non-verbally. It’s an exciting time. So what could we gain by asking patients to keep art diaries, or by inviting artistic responses to our questions? I’ll suggest four things:

- We offer an alternative voice to those who sometimes struggle to express themselves verbally. Patients with learning difficulties or linguistic impairment could particularly benefit in this regard.

- Visual art is immediate, visceral and emotive. Likewise, illnesses are often experienced immediately and through feelings (physical and emotional) rather than thoughts. Artistic expression gives patients the chance to depict their experiences in an appropriately abstract and sensory manner.

- The acts of speaking or writing will always carry some degree of social baggage – a subconscious sense that there is a correct thing to say and an appropriate way to say it. But artistic expression, by virtue of being outside most people’s usual methods of communication is virgin territory, free of any lingering sense of ‘I should do this’ or ‘most people would do that’. Patients are placed in a new expressive environment, and are free to take off in whichever direction seems suitable.

- We promote patient engagement. By asking for such idiosyncratic and emotionally-driven forms of response we demonstrate our interest in the patients’ personal journeys and individual feelings, drawing them deeper into the conversation and broadening the scope of their contribution.

Artistic response to illness, drawn by the patients: Suspected panreatitis

What you do with the responses you receive is up to you (though legal teams should be consulted wherever necessary, of course). Patient artworks can be integrated into films; blown up and exhibited at events and symposia to give HCPs and industry players a visceral, human and immediate window into the experiences of the patients they’re treating; included in printed materials; used online to stimulate patient discussion, or all of the above (and this list is by no means exhaustive).

Patient artwork is not without its own issues, of course. It’s tough to scale, the quality and format of responses will vary widely, and it can be very difficult to quantify or summarise this sort of data. Of course, it also won’t give the sort of precise and considered information that you’ll get from verbal engagement – it’s a complementary method. But I hope I’ve shown that it can represent a powerful arrow in the quiver of patient engagement techniques, and can function as an illuminating feature of patient-HCP-industry dialogue. The palaeolithic people of the Chauvet Cave answered their primal urge to create art – we have much to gain by doing the same.