Through the 1980s and 1990s antibiotic development was the pharmaceutical industry’s Cinderella. Coming from humble origins she had made it to the ball and married her prince. However since then things have taken a downward turn for our favourite fairy-story characters and the ugly regulatory and market condition sisters have sent Cinderella back to the shadows of the kitchen. The question now is whether she can make it back to the ball and become our princess once more?

The early years

It has been 70 years since the advent of commercially available antibiotics to fight the tide of bacterial infection. Their use across both animal and human populations is arguably the most important intervention in health ever by the pharmaceutical industry. Yet perhaps the industry’s greatest triumph has an Achilles heel.

The dawn of the commercial age

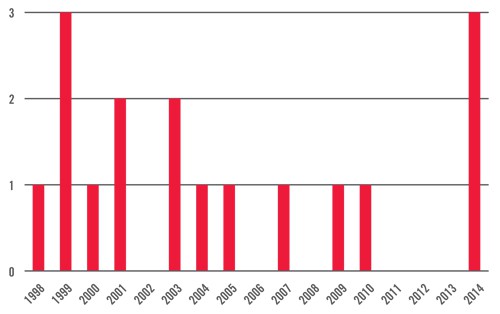

The commercial success of antibiotics once reflected the achievements of the pharmaceutical industry to develop a range of agents to keep a dazzling number of pathogens at bay. Through the 1980s and 1990s, this was the realm of the big pharma companies who dominated with huge R&D investment commensurate with commercially attractive therapy areas. Then, the pipeline dried up. From 1983 to 1987 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 16 new antibiotics, with a further 14 during 1988 to 1992. However, between 2008 and 2012 just two new antibiotics received FDA approval.

| FDA new antibiotic approvals | |

| 1983-87 | 16 |

| 1988-92 | 14 |

| 1993-97 | 10 |

| 1998-02 | 7 |

| 2003-07 | 5 |

| 2008-12 | 2 |

| 2012-13 | >3 |

There were three principal reasons for this. Firstly, the science hit the wall; the number of accessible targets which disrupted bacterial proliferation became exhausted, and the fundamental biology exposed our limitations of science. This was exacerbated in Gram-negative bacteria through their double cell wall, making cell penetration all the more difficult. The most obvious biological targets for antibiotics had already been identified.

Secondly, the economic deck of cards became stacked against antibiotic development. Through the 1990s and 2000s focus shifted to concentrate on relatively ‘easy’ commercial wins driven by chronic diseases driving several chronic therapies into blockbuster status, while encouraging a slew of profitable ‘me toos’. This marginalised antibiotic development where most patients would be managed with a short course of therapy often with a cheap generic antibiotic.

The third element of this perfect storm was the increased requirement to justify use of new antimicrobials. Antimicrobial stewardship encouraged doctors to reserve new effective antimicrobials for patients who ‘truly needed them’. This raised the bar to achieve return on investment, changing the sales forecasts of new antibiotics into slow burners which only generated significant revenues after several years in market. Bloodied by unfavourable profit and loss statements and scarred balance sheets the industry turned its attentions to richer financial pickings.

Encouraging a renaissance in product development

Medical and political rhetoric has now given way to decisive action. In the UK the Longitude Prize awarded for addressing societal challenges was this year granted to the development of rapid, reliable point of care diagnostics to enable more effective use of antimicrobials. This coincided with backing from the UK Prime Minister David Cameron who said: “This is not some distant threat, but something happening right now. If we fail to act, we are looking at an almost unthinkable scenario where antibiotics no longer work and we are cast back into the dark ages of medicine.”

Speeches detailing apocalyptic visions of a post-antibiotic era have now crystallised into fundamental changes to encourage development of new antibiotics. Those willing to play the game were handed an ace card in 2012 as the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act was signed into law, so too was the Generating Antibiotics Incentives Now (GAIN) Act. The GAIN Act is complex but broadly speaking, it gives five years market exclusivity during which the US regulator agrees not to approve a generic version of the candidate agent, even if it loses patent protection. For an agent with activity against qualifying pathogens, the FDA can give a QIDP designation which guarantees fast track review giving the possibility of rapid market entry and streamlining the regulatory process.

Systematic antibiotics – US approvals by year

Three antibiotics approved by the FDA in 2014 as of August 31

Finally, the burden of clinical development has been pared back with the FDA willing to consider trials in patient sub-populations reducing the size of phase III Trials needed to bring a drug to market. This has effectively given a mandate to the creation of a pathogen-focused antibacterial drug development pathway and should stimulate the creation of new drugs through clearer and more efficient data requirements to demonstrate efficacy and safety.

In Europe, the Innovative Medicines Initiative has gained traction with the COMBACTE (Combatting Bacterial Resistance in Europe) project which aimed to stimulate antibiotic development by pioneering new ways of designing and implementing efficient clinical trials for novel antibiotics. This coordination of effort should lower the burden of running clinical trials of sufficient magnitude to enable new product registrations.

Most industry commentators agree that the recent shifts in legislation are clear steps in the right direction. As John Rex, VP and head of infection, Global Medicines Development at AstraZeneca commented, “the whole tone of the conversation has gone from no, to go” and that has been reflected in recent shifts in the development landscape. Big pharma has once again started to crank up the antibiotic development machine with AstraZeneca, Roche, Novartis and GSK all returning to the arena, while another major company, Cubist, has outlined a clear company growth strategy entirely dependent on the success of its antibiotic portfolio.

Antibiotic development, it would seem, is once again back in vogue among researchers.

Challenges remain

Questions remain as to whether GAIN goes far enough. While the basic incentives are attractive enough to make antibiotic development ‘interesting’, it would seem that the current changes to legislation on both sides of the Atlantic fail to address the fundamental issues which caused the pipeline to dry up in the first place.

After decades of access to cheap effective antibiotics, healthcare commissioners have yet to develop the stomach to pay sufficiently high prices to justify companies bringing new agents to market. This is despite there being favourable health economic arguments for life-saving antimicrobial agents which effectively combat multi-drug resistant pathogens.

Can Cinderella attend another ball? It will take more than an intervention from her fairy godmother. In an increasingly financially pressured healthcare economy there is a need for a development pathway to reduce the risk of antibiotic development and provide front-loading lifetime revenues for new antibiotics coming to market. While the ‘slow-burner’ model of sales revenues acquiesces nicely with the model of effective antimicrobial stewardship, the truth is that this has little appeal to pharma executives looking to repair balance sheets, or for the small pharma start-ups risking all on the roll of the development dice.

Three agents approved for Gram-positive infections by the FDA in 2014. Progress in the treatment of Gram-negative infections has lagged somewhat but Cubist is expected to have its ceftolozane-tazobactam combination approved by the FDA in December, while AstraZeneca has submitted phase III clinical trial data for its ceftazidime/avibactam combination. However, significant challenges remain. GAIN has provided the wheels, but governments need to build the golden coach and provide the horses for Cinderella to attend the ball. The future otherwise might just be more bleak than can be imagined.

New hope

There is little doubt recent legislative developments have encouraged further investment in antibiotic development, however as the lure of commercial success attracts pharma back into the game, how will companies position themselves to maximise the opportunities? How can companies position their brands to not only achieve true market access, but also to align with effective antimicrobial stewardship? Might the answer lie in pathogen-specific clinical trial endpoints, and what role will point of care diagnostics play? Finally, can the agents which promise rapid infection resolution and the potential of patient management outside the hospital setting create compelling pharmacoeconomic arguments to justify premium pricing?

As the first agents designated as QIDP arrive at market in 2014 there is new hope for the Cinderella of the pharmaceutical industry, and companies willing and able to develop effective therapies will find their glass slipper and continue to attract more investment to safeguard against a new age of medicine.