| Executive summary | Generics |

| Introduction and overview | Biotech |

| Government | Marketing |

| Healthcare | Trends and outlooks |

| Pharmaceutical market |

Executive summary

- Germany boasts the strongest economy in Europe with upbeat forecasts for 2012, providing the Euro crisis does not worsen

- Chancellor Angela Merkel may well be penalised politically in the 2013 election for her management of the issue if it means Germans paying more to save the Euro

- The healthcare system is universal and highly decentralised, based on compulsory health insurance provided by sickness funds

- A controversial reform of the financing of public healthcare is under way to cut the link between employers’ contributions and rising healthcare costs and make it more equitable, limiting additional contributions. This will impact on pharmaceutical expenditure

- Germany is the third largest pharmaceutical market by turnover in the world, with sales worth €30.7bn ($40bn) in 2010

- 62 per cent of pharmaceuticals produced in Germany are exported, therefore this is a crucial area for the industry and vulnerable to what happens to the European currency

- A new law to restructure the pricing and reimbursement system, AMNOG, has led to the end of free pricing, with manufacturers having to prove the added benefits of their products, which is impacting the launch of new prescription drugs in Germany

- The R&D industry association is concerned with the negative effects of this reform on profitability and competitiveness

- The new ‘hostile’ environment for drug launch and pricing has a wider effect across Europe and further afield, because of Germany’s role as a reference price country

- The German generics market is by far the largest in Europe, with a market share of 70 per cent, plus the potential for biosimilars is growing in a positive environment for cheaper versions of patented products

- The biotech sector has the right conditions to grow, with government backing and scientific innovation knowledge, however venture capitalists are still shy of investing.

|

Overview Population: 81,702,329 |

Introduction

Germany bosts Europe’s second largest population (after Russia) and the strongest economy. It ranks fifth in the world in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms. Since unification in 1990, Germany has spent considerably to harmonise productivity and wages across the country and prosperity has increased on the back of German exports, particularly of machinery, vehicles, metals, chemicals and other goods needed in emerging markets. Despite massive funds being poured into its economy, the former German Democratic Republic still lags behind, with people in the West resentful for paying more than they initially expected.

Germany was one of the founding members of the original European Economic Community, which evolved into the European Union, and it launched the Euro in 1999 with 10 other member states, becoming the continent’s economic giant.

Germany does not have one single economic centre, but as a federation it has several industrial centres, such as Stuttgart, Munich, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Leipzig and Bremen. Its small-to medium-sized manufacturing firms, or ‘Mittelstand’, specialise in technologically advanced goods and are often family-owned.

Germany’s main risk to stability is the Eurozone debt crisis, which could impact economic growth and have serious political implications.

The 2008-2009 recession hit Germany hard at first, but it recovered quickly due to fiscal discipline, rebounding manufacturing exports and policies to maintain low unemployment. Domestic demand has been growing significantly after stimulus packages and tax cuts introduced by the current government, while reducing the deficit.

Like other developed nations, Germany faces challenges to sustained growth due to an ageing population, low fertility rate and a decline in immigration. Welfare and healthcare spending at the current level may not be viable to sustain growth.

In the last quarter of 2011, the German economy actually shrank by 0.25 per cent, according to the German Federal Statistics Offices. However, for the whole of 2011, the economy grew by 3 per cent.

Investors still see Germany as a solid proposition even in a Eurocollapse scenario and with good reason: unemployment has fallen to a post-reunification low of 5.5 per cent and it has a current account surplus of 5 per cent of GDP.

Economist Jan Randolph, director of Sovereign Risk at IHS Global Insight told PME: “Germany represents nearly one third of the Eurozone GDP economy and it is the region’s wealthiest and most competitive country … The Germans now recognise that austerity alone will not solve the debt crisis – there also have to be measures to boost long term growth prospects and to generate more jobs.”

In the report ‘Economic Assessment of the Euro Area, Winter 2010/2011’, The Kiel Institut forecasts: ‘We expect that growth in investment will resume in the course of 2012, and private consumption will stabilise domestic demand through the year. Exports to Western Europe will suffer but exports to the rest of the world are expected to continue rising … in 2013 the German economy will gain renewed momentum, although the high growth rates of 2010 and 2011 will not be repeated.’

Government

Germany is a Federal Republic composed of 16 states, each with its own constitution. It is a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper chamber, the Federal Council, or Bundesrat, and the lower chamber, the Federal Diet or Bundestag.

Chancellor Angela Merkel of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) has been in power since 2005, first presiding over the ‘grand coalition’, an awkward alliance of the CDU, Christian Social Union (CSU) and the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SPD). In 2009, she managed to secure enough votes to form a government with traditional allies CSU and the Free Democrats (FDP).

Since the Euro crisis, Germany faces the prospect of having to make huge contributions to bailouts to help indebted countries and rescue the European currency. The CDU lost heavily in regional elections in 2010 and 2011 and as a consequence, Angela Merkel’s party no longer has a majority in the Bundesrat. This has been interpreted as a strong message from the German people that they resent what they see as an unfair financial burden.

Chancellor Merkel has proposed a new system of financial regulation within the EU. A fiscal union backed by a new treaty will allow the EU to veto national budgets in the Eurozone that violate the so-called ‘golden rules’ regarding deficits.

The German government suggested quasi-sanctions for countries that surpass agreed debt levels and for the European Court of Jurisdiction to have jurisdiction over disputes. But partners in Europe say that Germany must be more generous to avoid the collapse of the Euro. The International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank want to bolster the bailout fund to regain the confidence of the markets. However, 25 out of 27 EU countries have agreed to follow the German-inspired solution, although a treaty would have to be ratified; a major hurdle.

Healthcare

Life expectancy has increased by four years for women and five years for men in the last 20 years, reaching an average of 80.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), Germany’s disease profile reflects its high income status with heart disease and stroke the most common causes of death, followed by cancer, particularly lung and colon. The general cancer mortality rate is lower than the EU average but slightly higher for breast cancer. Communicable diseases account for just 5 per cent life years lost. Around 24 per cent smoke, which is relatively high and the obesity rate at 14.7 per cent (self-reported weight and height data) is a cause for concern. At almost 9 per cent, the diabetes rate in the 20-plus group places Germany fourth after US, Canada and Mexico.

Top 10 causes of death

| Deaths total | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number | per cent | |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease | 72,734 | 8.5 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 55,541 | 6.5 |

| Heart failure | 48,306 | 5.6 |

| Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | 42,972 | 5.0 |

| Other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25,675 | 3.0 |

| Stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction | 23,675 | 2.8 |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 20,604 | 2.4 |

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 18,391 | 2.1 |

| Malignant neoplasm of breast | 17,573 | 2.0 |

| Malignant neoplasm of colon | 17,161 |

2.0 |

Source: German Statistics Office, 2012 (excludes stillborn cases and judicial causes)

To respond to ageing of the population, a long-term care insurance scheme was created in 1995.

The number of doctors and nurses per 1,000 inhabitants is high but fewer medical professionals are graduating, leading to a recruitment issue. The government has been reluctant to allow healthcare staff from other EU members to practice in Germany but it has changed the rules of preference (that jobs go to German nationals first) and created a package to ‘attract foreign talent’.

Last year, electronic health cards were introduced, containing administrative data about each patient, plus a chip for more sensitive personal medical information to be stored and safely exchanged between health providers. Patients will be able to choose which data is encoded and access their own files.

Germany has the oldest universal healthcare system, dating back to the Bismarck Republic social legislation. It is financed by the government through taxes and private contributions to sickness funds (Krankenkassen) or social health funds, where employees’ wages are deducted. The scheme was for low income and public sector workers but has been expanded to cover the majority of the population. It is divided into the Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung (GSK), the mandatory basic health insurance for employees earning up to around €50,000/year (around 85 per cent of the population), which can be supplemented with private plans, with the remaining 15 per cent having private health insurance.

These high income workers and selfemployed professionals choose to pay a tax and opt out of the public system, taking out private policies. However, they can only rejoin the public healthcare service before they reach 55 years of age and if their income drops below a certain level.

Public healthcare is ‘pay as you go’ and covers family members and does not depend on age or health status.

Highly decentralised, the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) service is run by doctors at practice level and most hospitals are non-profit organisations offering in-patient care. Others are publicly run or private. Another feature of the healthcare system is privatisation, particularly in the ambulatory sector and pharmacies. In the hospital sector, private, public and not-for-profit providers coexist.

Since 1976 the government has convened an annual advisory commission, composed of representatives of business, doctors’ unions, hospitals, insurance funds and pharmaceutical industries. This ‘Concerted Action in Healthcare’ collects and presents data on the medical and economic situation regarding the healthcare system. At state level, health is usually part of other ministries such as Labour and Welfare. State governments are responsible for hospitals and public health services, as well as undergraduate medical, dental and pharmaceutical education, as well as supervision of local sickness funds.

Patients can visit any doctors they wish and compare sickness funds to find the best deals. They penalise bad service and have high expectations of the healthcare system, though, until recently, most were satisfied with the services provided. Consultations with specialists do not have to be referred by GPs and patients can see different GPs. The government has tried to reduce costs by introducing an out-of-pocket modest fee to see a doctor, charges for non-prescription drugs and cuts on free alternative medicine.

At federal level, the key player and decision maker is the Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gensundheit, BMG).

Attached to the BMG is the Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (BfArM), the major licensing body for pharmaceuticals, supervising the safety of both pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Biomedicines, vaccines and sera are licensed and supervised by the Paul-Ehrlich-Institute. In many cases, authorisation of medicinal products is granted by the European Commission in a centralised authorisation procedure.

Compulsory insurance is paid for by joint contributions from employers and employees and negotiated in complex corporatist social bargaining at state level. The Health Insurance Funds are mandated to provide a wide range of coverage and, since 1996, patients can choose which fund to join and move between funds. Sickness funds offer benefits packages covering prevention, screening, treatment and sick pay not covered by employers.

In the 1990s, caps on expenditure were introduced to keep costs down, since Germans visit the doctor quite often (more than six times a year). Plus, the average hospital stay is nine days (OECD data) compared to 5 to 6 days in the US.

The strict separation of the ambulatory and the hospital sector has also been loosened and there is more cost sharing. The purpose was to reduce expenditure for dental care, physiotherapy and transportation, to make the patient liable for pharmaceutical costs above reference prices and to reward ‘responsible behaviour’ and good preventive practice with lower co-payments.

According to the German Federal Statistical Office, healthcare expenditure totalled €278.3bn in 2009, increasing 5.2 per cent compared to 2008. It corresponded to 11.6 per cent of GDP (10.7 per cent a year earlier). The public healthcare bill has increased significantly since reunification and the hospital sector is the most costly. Administrative fees represent a third of the bill, according to the BMG and around 15 per cent is spent on pharmaceuticals.

The Economist Intelligence Unit expects total healthcare expenditure to rise by an annual average of 2.8 per cent in 2012-16, to reach around €335bn in 2016. The pharmaceutical industry bodies have warned however, that the SHI drug market is stagnating and that effective spending decreases with cuts in expenditure.

Pharmaceutical market

With a tradition of invention in the medical field that brought aspirin, Germany has been an attractive pharmaceutical market for years. It is the world’s third largest pharma market behind the US and Japan, with sales worth an estimated €30.7bn in 2010. A total of 62 per cent of pharmaceuticals produced in Germany are exported. Many manufacturers are family-owned businesses, such as Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and Merck, or are still controlled largely by members of the founding family.

The market is fragmented, although some consolidation happened when Bayer bought Schering. Current trends are for big firms that invest heavily in R&D, such as Bayer, BI and Merck KGaA, to make alliances, cutting costs and avoiding becoming targets themselves. Schwarz Pharma was taken over by Belgian company UCB in 2006.

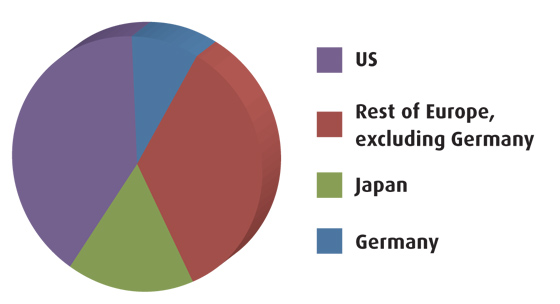

German R&D expenditure in 2009

Source: EFPIA, PhRMA, Vfa, provisional data

The large, R&D multinational companies have formed their own organisation, the Association of Research-based Pharmaceutical Companies, Vfa, splitting from the existing Federal Association of the Pharmaceutical Industry (representing smaller companies) because of disagreements over reimbursable lists and prescription exclusions.

The German drugs directory (Rote Liste) listed 8,500 products in 2010, but according to health insurers’ evaluations only around 2,000 are prescribed.

Last year, critical changes occurred in the German pharmaceutical market, one of the last liberal drug pricing bastions in Europe: a price moratorium until 2013 and a mandatory discount for patented medicines supplied to the SHI (from 6 per cent to 16 per cent) had had some impact, but the main upheaval was a new law on the Restructuring of the Pharmaceutical Market in Statutory Health Insurance (AMNOG), which came into force in January 2011.

When a product is launched, the manufacturer must prove its added therapeutic efficiency or it will be included in the reference pricing list, regardless of the existence of alternative generics.

Orphan drugs are excluded, as well as hospital-only drugs and those that have a limited budget impact on the SHI. This legislation is meant to ‘create a new balance between innovation and affordability of medicines’, according to the Ministry of Health. It aims to boost competition and ‘curb spiraling expenditure for medicinal products’, bringing savings of about €2bn a year.

The law stipulates that pharma companies must prove additional benefits of new medicines in order to justify prices, effectively ending free pricing. It abolishes the reward and penalty points system and the requirement for a second opinion when prescribing costly drugs. The Ministry describes it as more ‘patient friendly’.

Pharma companies have a year of leeway with their chosen price and have to negotiate reimbursement prices with health insurance funds and, if no deal is brokered, the medicine undergoes a cost assessment analysis by Germany’s health technology assessment body, the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG).

Under AMNOG, the level of added therapeutic benefit granted to newly approved drugs is based on a scoring system of 1 to 6:

1. Major added benefit over comparator

2. Significant added benefit

3. Slight added benefit

4. Unquantifiable added benefit

5. No added benefit proven

6. Less than comparator.

It is significant that last year, BI and Lilly decided not to launch their new diabetes drug Trajenta in Germany, blaming price controls.

According to IHS Global Insight, a year on 10 therapies had gone through assessment by the German watchdog, the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA). Pharma analyst Anne-Charlotte Honore, writes: ‘the stringent selection of the cheapest appropriate comparator is set to represent a significant hurdle for pharma market access in Germany.

Out of the 10 products assessed last year, four have obtained poor innovation scores: Esbriet (pirfenidone), Livazo (pitavastatin), Yellox (bromfenac) and Trajenta (linagliptin) and a majority of manufacturers have struggled – sometimes declined – to provide comparative data versus the appropriate comparator selected by the G-BA.’

More recently, the added benefit of fixed combination aliskiren/amlodipine (Novartis’s Rasimamlo to treat hypertension, approved by the EU in 2011) was also deemed ‘not proven’ by the Federal Joint Committee and the same ‘no proof’ decision was reached regarding GlaxoSmithKline’s Trobalt (retigabine) for epilepsy. Novartis discontinued its marketing of Rasimamlo in Germany.

The new law seriously impacts the German market and causes a ripple effect in wider Europe because Germany is a reference price market for many countries. According to IHS Global Insight, downward pressure on prices will probably be felt in Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Switzerland and Taiwan. The idea is that companies will now have to focus on ‘real innovation’, say regulators. The perceived level of added clinical benefits as price driver is also being applied in other markets, such as France and Austria.

Germany introduced a reference pricing system in 1989 defining reimbursements thresholds for groups of pharmaceuticals. It is a therapeutic referencing, as in the Netherlands where substitution goes beyond products with the same active ingredient to different molecules for the same indication, but its effectiveness as a cost-cutting tool is limited. Early studies showed manufacturers dropped prices to the level of the reference price and it was not comprehensive.

In 1996 new on-patent medicines became exempt unless they were part of classes such as statins to control the impact on spending on ‘me-too’ drugs. The national drug budget of 1993 stipulated spending limits for outpatient prescription drugs. In 1997, this system was replaced with prescribing guidelines for doctors threatening with repaying if budgets were overrun. The drug budget was abolished in 2002 but the potential threat of penalties has coerced doctors to be more price sensitive with prescribing. In 2009 and 2010, around three quarters of all pharmaceuticals prescribed in Germany were subject to reference pricing, due to widening of the scheme.

Prices are negotiated with the federation of health insurers and not individual funds. The R&D association, Vfa, expressed concern that taking individual sickness funds out of the equation may create a monopoly and focus excessively on cutting costs.

Pharmaceutical sales of branded products have weakened as a result of the bill and continued penetration of generics, but they are expected to rebound given the ageing population and the new range of therapies available. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Germany’s total pharmaceutical bill is estimated at €29bn in 2011. It forecasts a rise to around €33bn in 2016.

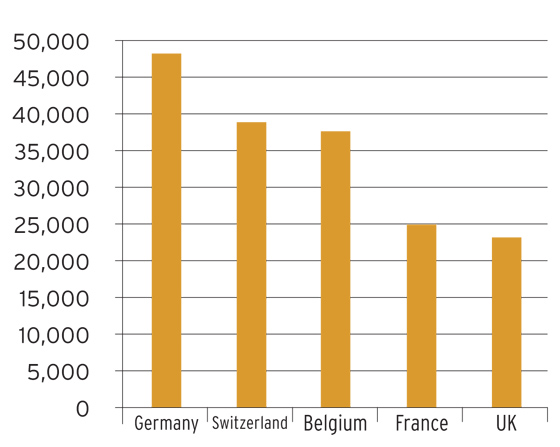

Pharmaceutical exports (€m)

Source: EFPIA, 2009

According to Vfa in 2010 only 26 new molecular entities were launched in the German market, compared to 36 in 2009. Vfa says that the new law will make the situation worse. Siegfried Throm, director for innovation at Vfa, told PME:

“With respect to R&D, the framework conditions in Germany are still very encouraging. For example, for many years Germany has ranked second worldwide regarding the number of clinical trials and the number of sites, which is a result of the following factors – good research locations, highly skilled researchers, excellent quality of research data, reliable and well-functioning regulatory processes … Yet, the positive environment for R&D is challenged by the recent measures of the Ministry of Health, especially the early benefit assessment. Used purely as a cost-containment tool this measure poses a severe burden on the pharmaceutical industry in Germany, which might have an adverse an effect on R&D location in the long term.”

Vfa claims that up to 2003 prices for pharmaceuticals barely changed but since then they have decreased significantly. Pharmaceuticals are now 10 per cent cheaper than they were in 2000. Medicines are also subject to a 19 per cent value-added tax, which, combined with mandatory price cuts, is eating into profits. The VAT charged in Germany is the third-highest in the EU, after Denmark and Ireland.

Sales increased slightly in 2010 in the SHI market, driven by a demand in consumption and by innovative medicines (€900m and €480m, respectively), although the industry predicts a decrease, as a result of expenditure cuts. Generics and increased discounts impacted on sales of branded products, leading to savings for the SHI of €430m and €800m, respectively.

Generics

Germany’s strong and growing generics market is the largest in Europe. In the public system it accounts for 30 per cent in value and 60-70 per cent in volume. Since 2004, incentives have been given to pharmacies to offer generics and substitution is usually compulsory.

The R&D industry association claims Germany is the ‘the most generics-friendly country in the world’ and that their actual share is 80 per cent. ‘Original products often lose almost their entire market share to generic drugs within a few months after a patent expires. An average of over 86.5 per cent of prescriptions and around 78.4 per cent of sales in the generics-eligible market were generated by imitation products in 2010,’ argues the Vfa report ‘Statistics 2011, the pharmaceutical industry in Germany’.

In November 2011, generics firm Stada Arzneimittel announced a deal to acquire Switzerland-based Spirig Pharma’s generics business for approximately €78m. Earlier in the year, it entered a partnership with Hungary-based Gideon Richter to collaborate on biosimilar development of monoclonal antibodies. In 2010 Israel giant Teva bought one of Germany’s top-companies in the generics market, Ratiopharm.

A subsidiary of Novartis and big player in Germany, Sandoz is second in the world after Teva, now top supplier of generics to the largest health insurer.

There is a trend towards price regulation in the generics market with rebate contracts, introduced in 2007, in which the SHI negotiates an exclusive deal with a supplier based on best price, generating considerable turnover for smaller firms.

Biosimilars or follow-on biologics are also taking off, with favourable prescription and dispensing requirements after the EU guidelines for biosimilar approval have been issued. For instance, the launch of EPO has contributed to considerable public savings.OTC drugs are sold in pharmacies only (some herbal medicines and supplements can be sold in other stores) and comprise around 12 per cent of the pharmaceutical market, according to Vfa. The abolition of price controls for OTC pushes prices down, as demand is not expected to increase. Substitution by prescription reimbursable medicines takes place when appropriate.

Biotech

There are biotech clusters in Munich, Heidelberg and Cologne, and companies in this sector have had government support, although government regulations, for example on the use of stem cells, remain restrictive. The German Stem Cell Act was amended in 2008 to allow the import of cell lines harvested before May 1, 2007, although there is a general ban on creating and working on human embryonic cell lines.

Germany ranks lower than other European countries on innovation, despite its pioneering successes in the 1970s and heavy investment by companies, particularly big pharma. To increase competitiveness, the German federal government created BioREgio in the mid-1990s, a contest with financial rewards for the strongest biotech regions.

After a short boom and bust period, the government launched the ‘Pharmaceuticals Initiative for Germany’ in 2008 to stimulate the sector through partnerships, focusing on clinical trials, allocating R&D grants, interest-reduced loans and special partnership programmes. Each state also has its own R&D grant programmes for small and medium sized companies.

Today, biopharmaceutical sales account for 16 per cent of the German pharmaceutical market and are expected to grow up to 20 per cent by 2020. Despite the excellence of German scientific research and business practices, the industry suffers from lack of investment due to risk aversion and a negative image. In a study, Klaus Weber and colleagues claim that the anti-biotech social movement, led by the Green party, altered the public perception of biotechnology, by concentrating on the potential dangers of using genetically-engineered techniques to manufacture drugs. (‘The Fall of German Biotech-How the anti-biotech movement tripped up once-pioneering firms’, January 2011, Kellogg Institute School of Management). This created credibility problems with investors.

Around 80 per cent of biopharma sales fall into applications in metabolism (especially insulins for treating diabetes), immune-mediated diseases, cancer and disorders of the nervous system.

The Heilmittelwerbegesetz (HWG) (Law on Advertising in the Field of Healthcare) governs pharma advertising, which is only permitted to medical professionals. The communication activities of pharma companies are also considered advertising under the law, which is challenging for the marketing of prescription drugs. There are also selfimposed restrictions on marketing, with voluntary ethical guidelines outlined by the R&D industry association, Vfa.

Communications materials must be drafted within these tight legal limits, where the product cannot be named if patients or public audiences are addressed directly. The press can mention the generic name of the medicine, although this is also becoming more difficult, due to changes affecting the media, both financial and in terms of content.

Media relations remains an important and intensive part of the general marketing strategy.

Campaigns aimed at physicians to promote new products are appropriate but reaching patients is only possible through disease awareness initiatives, as only indications and balanced information about all therapeutic options can be mentioned.

Another challenge is to tailor communications to each relevant healthcare professional target group, as there is a huge diversity of specialities and conditions, with an array of professional bodies and associations.

In the new regulatory landscape, communications have to start much earlier, in the pre-launch phase, with communicators thinking laterally and treading carefully.

Jens Gruenert, managing director of inVentiv Health Communications Germany (Munich), told PME: “AMNOG will definitely have a deep impact. Until the law was implemented, Germany was a good country for product launches. Now companies will think twice. The pharmaceutical industry needs to respond to the rapidly changing market and policy environment. In order to succeed, they need targeted and flexible marketing solutions.”

Doctors and patients want more tailored solutions and a more personalised approach: “Drugs are not being sold to a broad patient group, but need to take into account individual patient needs.

Revenue streams are decreasing and so, as a result, are marketing budgets. We are moving away from key messages around a product to providing services that add value to doctors and, as a consequence, to companies. For instance, in the hypertension market we are developing a patient support portal for disease management that save doctors’ time and reduce their overall efforts in monitoring the condition,” Gruenert continues.

iHCE notes that classical advertising work is decreasing, with strategic consulting becoming much more relevant: “We try to strategically advise the client, working together in brand planning and finding the appropriate marketing tools that are most valuable. iHCE teams first consider the challenge then draw upon an unrivalled breadth of talent and expertise to create multi-disciplinary and channel solutions delivered through a fully integrated team. Most companies realign their marketing globally to deliver brand consistency across multiple markets, whilst maximising local buy-in and creativity, delivering financial savings,” observes Gruenert.

Communications activities are becoming even more diversified because there are multiple decision makers alongside healthcare professionals. The recent launch of iHCE, a full-spectrum healthcare ‘super agency’, illustrates the need for a cost-effective and actionable multi-disciplinary approach to reach and motivate target audiences with greater speed and relevance.

“The promotion of a healthcare product or service is not just about branded promotion. It is about communication and dialogue with a diverse set of stakeholders who have a variety of needs and consume information through multiple channels,” states Damon Caiazza, head of advertising at iHCE.

Susanne Buder from Haas & Health Partner Public Relations, part of inVentiv Health Communications Germany (Frankfurt), describes the environment as: “Extremely complex. It is not easy for the pharmaceutical industry to stand out from the crowd and differentiate itself from competitors effectively. It is all about educating doctors and collaborating more with companies and third-party groups from an earlier stage. Pharma companies are trying to work in partnership and are not just interested in selling drugs any more. Companies understand and recognise the need to communicate early through increased information and disease awareness initiatives, so that we can build pressure in the marketplace.”

Holger Pohlen, managing director at SanCom Creative Communication Solutions, part of inVentiv Health Communications Germany (Frankfurt), agrees. He told PME: “Campaigns have to be more international and open-minded. We need to be more creative when looking for editorial space and show engagement with all different groups.” Susanne Buder adds: “We recommend an integrated approach. Get all the scientific data, understand the product and the challenges and create the right communications strategy to bring return on investment. Basically we need to be ahead of the curve.”

The ‘Cybercitizen Health Europe’ study by Manhattan Research revealed that people looking for information about pharmaceutical companies and their products are receptive to websites but not so keen on social media communications for that purpose. Germans were the least interested to learn about prescription drugs from pharma companies, perhaps revealing distrust of the industry.

Caiazza clarifies: “While German physicians may be the least interested, it doesn’t mean they aren’t consuming information digitally.

Usage is increasing across all digital channels. Digital-based communications and programmes account now for more than 50 per cent of our business. In addition, there is a growing emphasis on medical education and communications as well as focused activities on the valueadded services that have been built up around most major brands.”

Andreas Reinbolz, senior vice president digital strategies & innovations at inVentiv Health Communications Germany (Freiberg) told PME that with shrinking budgets and diminished sales representative forces it is becoming increasingly hard to target doctors, which may not have been the case in the past: “They now need to be more selective.

Digital channels allow reps to adapt to GPs’ needs, with instant access to clinical data, guidelines, publications, training, webcasts and websites to back up product information. The hybrid model is more commonly used now, where reps visit less face-to-face and contact remotely using different platforms, although physical meetings are important when wanting to go beyond key messages and build strong relationships.”

Therefore, digital tools are used for direct interaction, remote contact and a hybrid of the two when addressing medical professionals.

Nearly 50 per cent of doctors use social media, so there are opportunities here, but restrictions in promotional tools still apply and content needs to be maintained and monitored. Growing communities, such as closed networks for doctors, are becoming more important as target audiences.

Patients are not as involved in the process of accessing information or requesting particular drugs, with the exception of the MS association, for which inVentiv Health Communications Germany (Freiberg) built a moderated forum that has successfully furthered its purposes as an activist patient group.

The use of smartphones is also widespread in Germany for divulging and accessing medical information online. “Mobile is a huge trend,” explains Reinbolz. “Sometimes clients want apps because that’s what everyone is doing, but there are good reasons to use this technology through providing tailored solutions that help patients and doctors.

For example, apps to help patients adhere to treatment and doctors monitor the results can have significant impact. Building pain diaries helps people understand the benefits of the treatment. It can also be used as a diagnosis tool.”

Doctors are sensitive to interference, so they need to feel that these tools help to make their jobs easier.

Trends and outlook

The full impact of the new restructuring law is still to be assessed, but each medicine´s innovation level will now have a significant impact on market access strategies in Germany and in countries tagged to its reference pricing system. There are strong signs that companies may be reluctant to launch new products in Germany to avoid the extra regulations and lengthy price negotiations. The Euro crisis also adds to this worrying scenario for several reasons: economic and political instability affect the industry, more bailouts will deplete public finances leading to more healthcare budget cuts and above all there is the fact that German pharma is highly dependent on exports.

However, the general business environment, plus the traditional innovative and adaptable nature of the R&D industry are still attractive propositions in a mature and solid market. The ageing population will need new and more effective therapies, particularly in oncology, heart disease and Alzheimer’s. But a shrinking labour force will mean fewer contributions to sickness funds. This model worked well once but is becoming stretched and outdated. Out-of-pocket contributions are likely to increase, as treatments become more personalised and the private sector may take more patients who can afford total freedom and access to the latest therapies.

Generics represent a strong segment, useful as a cost containment tool and well established with doctors and patients receptive to the message that they bring savings, although price controls are also stringent. Biosimilars are also growing and have been favoured by the same cost cutting policies that have boosted generics, now with legal backing from the EU.

Up to 2010, Germany ranked as the fifth best place for pharma after the US, Australia, Canada and Japan, according to Business Monitor (Business Environment Rating) but it is losing ground.

The biotech segment can be a success if more venture capital is found, as the German government is supporting innovation through generous grants, even if price restrictions and stricter regulations will affect all new products being launched.

The Author

Catarina Féria Walsh is a freelance journalist specialising in the pharmaceutical industry.