Recent clinical trials have offered hope that a disease-modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease could become available soon. Such a therapy would treat the disease at an early stage to prevent or delay the progression to dementia.

However, research from RAND and the University of Southern California that was sponsored by Biogen has found that several European countries lack the capacity to rapidly move a disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease from approval into widespread clinical use. This could significantly delay access to care and cause one million additional people to develop full-blown Alzheimer’s dementia while on waiting lists.

We developed a simulation model to examine the preparedness of the health systems of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The model projects what would happen if these countries were confronted with a surge of patients seeking evaluation and treatment, assuming a potential treatment becomes available in 2020. These six countries represent 65% of the European Union’s population.

Background

Currently, there is no Alzheimer’s disease- modifying treatment available but there are several therapies in development. After some encouraging early-stage clinical trial results, there is cautious optimism that a therapy may become available soon.

Based on results from early-stage clinical trials, therapeutic development has focused on the hypothesis that Alzheimer’s dementia must be prevented rather than cured, because candidate treatments have not been able to reverse the course of dementia. That’s why current trials target patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease by first screening them for signs of early-stage memory loss, or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), conducting tests for the Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and then treating patients with the aim of halting or slowing progression from MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease to Alzheimer’s dementia.

If this therapy were to become available, 20 million Europeans would need to be screened for MCI, evaluated for Alzheimer’s disease, tested for biomarkers (via cerebrospinal fluid assays or brain imaging) and treated with intravenous infusion therapy.

Our model

In our model, we assume that individuals aged 55 and older could undergo cognitive screening via a short instrument in a primary care setting. Patients whose screening tests are positive would be referred to a dementia specialist for neurocognitive testing and possible referral to testing for the presence of biomarkers related to Alzheimer’s disease.

Patients who test positive would return to the dementia specialist for further evaluation to confirm whether treatment would be indicated and appropriate. If appropriate, they would be referred to treatment, which would reduce the risk of progression from MCI to manifest dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.

This is the same model we used previously to analyse the preparedness of the healthcare system in the United States to handle the potential caseload if a disease-modifying therapy becomes available. We found that in the US there would be long waiting times for dementia specialist visits initially, followed by considerable waits for biomarker testing to confirm the Alzheimer’s pathology, and moderate waits for infusion delivery of the therapy. This would ultimately result in 2.1 million patients developing Alzheimer’s dementia between 2020 and 2034 (about 13% of the potentially avoidable new cases in this period) while on waiting lists. As other countries could face similar infrastructure challenges in diagnosing and delivering treatment to people with Alzheimer’s disease, we applied this model to six key European counties.

Europe is unprepared

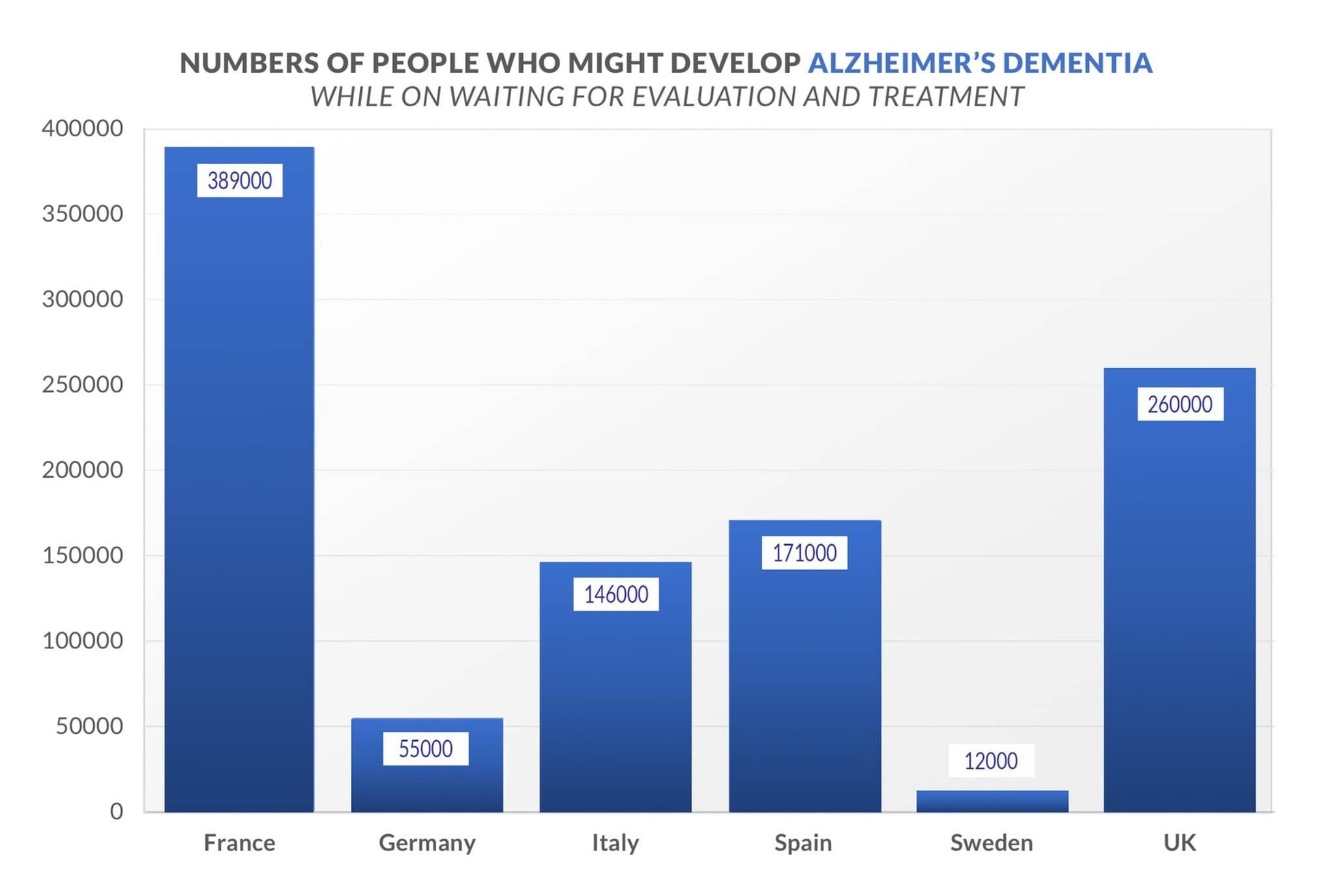

Our study assumes that a therapy is approved for use beginning in 2020 and estimates that under such a scenario about 7.1 million people with MCI would need timely diagnosis by a specialist. After follow-up evaluations and biomarker testing, we estimate that 2.3 million people in the six countries ultimately may be recommended for treatment. However, delays in this evaluation process as well as delays in intravenous infusion of the therapy could result in more than one million patients developing Alzheimer’s dementia while waiting for evaluation and treatment between 2020 and 2050.

In France, 389,000 people might develop Alzheimer’s dementia while waiting for evaluation and treatment. In Germany, it would be 55,000 people; in Italy, 146,000; in Spain, 171,000; in Sweden, 12,000; and in the United Kingdom, 260,000 (see graph).

The primary capacity constraint is the lack of medical specialists trained to diagnose patients who may have early signs of Alzheimer’s and confirm that they would be eligible for therapy to prevent the progression of the disease. Some nations have too few medical specialists and may require additional training of health providers. There are also too few facilities with capacity to deliver infusion treatments to patients.

The projected peak waiting times for treatment range from five months in Germany to 19 months for evaluation in France. The first year without waiting times would be 2030 in Germany, 2033 in France, 2036 in Sweden, 2040 in Italy, 2042 in the United Kingdom and 2044 in Spain.

We found that each country also had a unique set of capacity constraints. In Germany and Sweden, the main infrastructure constraint would be infusion capacity. In the other four countries, waiting times caused by both specialist availability and infusion capacity would delay treatment for more significant numbers of patients. Specialist capacity is the primary rate-limiting factor in France, the United Kingdom and Spain. In addition, innovation in diagnosis and treatment delivery would help ensure that sufficient capacity is created to treat patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

The way forward

While many European countries are unprepared, there are some promising efforts underway. France has a national plan that aims to improve care pathways for patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Italy has launched a project to identify patients with the highest risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia to improve coordination and timeliness of care. An understanding of Pharmaceutical Market Europe January 2019 the characteristics of patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease is vital to efficiently identify patients who could benefit from a new treatment.

A therapeutic agent would require near-monthly visits to administer an intravenous infusion, and most European countries may not have the capacity to provide infusions to all eligible patients in a timely manner. However, there may be two relatively near-term solutions: building dedicated infusion centres as extensions to existing facilities and using home infusions, if possible based on the therapy’s safety profile. Dedicated outpatient infusion centres may be built in cooperation with hospitals, memory clinics and other healthcare facilities.

In the past, specialised infusion centres have been established to provide outpatient infusion therapy administered by nurses to multiple sclerosis patients in Germany. Similar centres could be established for MCI patients if a new therapy becomes available, with specialised nurses trained in intravenous administration, oversight by physicians and patient education.

It is crucial that European countries begin to have a discussion now about how best to address these obstacles so that they are better prepared if and when an Alzheimer’s breakthrough does occur.

Importantly, nations should:

- Establish clinical pathways to screen for cognitive impairment and develop better detection tools

- Utilise dedicated outpatient infusion centres in collaboration with hospital, memory clinics and other facilities

- Ensure appropriate reimbursement of services

- Create EU-wide guidance and best practices for Coordinated and timely care.

This new study provides an important wake-up call to all stakeholders in European healthcare systems. Healthcare leaders in the European Union should begin preparing for a breakthrough now. Without advanced planning, we cannot ensure that all EU citizens who could qualify for evaluation and treatment can reap the benefits if such treatment does become available.