Bluebird Bio is just weeks away from gaining its first ever approval for its first ever product, Zynteglo, a groundbreaking gene therapy treatment for beta thalassemia.

But before it can launch the product in Europe, it must also become a pioneer of a new kind of sustainable pricing for gene therapies with Europe’s healthcare systems.

The European Medicines Agency’s CHMP committee recommended conditional marketing authorisation for Zynteglo (autologous CD34+ cells encoding β A-T87Q-globin gene) at the end of March, setting it up for a likely full European Commission approval by the summer.

The company has been a leader in gene therapy development, and has spent a decade of trial and error in developing the one-time treatment which promises to cure the rare blood disorder in many patients.

However, its leadership knows that this and other revolutionary gene therapies can’t be launched without forging a new type of partnership with healthcare systems – simply in order to manufacture and administer these hi- tech drugs. Moreover, it also needs to build trust about what healthcare systems can expect in terms of results and possible cost savings – and how to pay for price tags that are likely to exceed €1m ($1.12m).

All this points to a revolution brought about by cell and gene therapy, not just in clinical care, but also in the pricing and reimbursement framework to support it.

Chief executive Nick Leschly (below) said Bluebird is aiming to be a leader on both fronts.

Presenting his vision for the future at the JP Morgan meeting in January, Leschly said: “Our goal is to recode for life. It’s a big statement, a big dream, a big vision. And one we take very seriously.”

This ‘recoding’ of pricing and reimbursement deals with payers is essential for a number of reasons, but most immediately because of the huge upfront cost of gene therapies. Bluebird has floated what it calls an ‘intrinsic’ or ‘ceiling value’ for Zynteglo of around $2.1m.

The company has indicated the price will be significantly lower than this, although it could well be over that €1m mark.

Gene therapy failures

The industry and Europe’s healthcare systems are wary of that magic one million threshold, thanks to the failure of the first ever gene therapy, UniQure’s Glybera. Approved by the EMA in 2012, the rare disease treatment was priced at over €1m, and proved to be a commercial flop – partly because of its less than stellar efficacy, but also because of very limited manufacturing capability. GSK’s Strimvelis for ADA-SCID (Severe Combined Immunodeficiency due to Adenosine Deaminase deficiency) followed in 2016, and was a similar commercial failure.

The sector’s new leaders believe they have learnt from these failures – both in guaranteeing impressive clinical results, including potential cures, and in developing more sophisticated manufacturing and administration, and pricing agreements as well.

Bluebird is not the only company likely to break through this €1m barrier in 2019 – Novartis’ SMA gene therapy Zolgensma is also on the cusp of approval in the US. Novartis has suggested a similar intrinsic value for its therapy at $4m, although it is likely to set a price closer to $2m. Unlike Novartis, however, this is Bluebird’s first ever launch on the market, making its move a huge leap of faith for the Boston-headquartered firm.

The success or failure of Bluebird will be closely watched by a slew of cell and gene therapy companies including Sangamo, BioMarin (with exciting potential cures for haemophilia) and UniQure, looking to learn from its own mistakes with therapies for Huntington’s disease and also haemophilia.

It’s clear that companies like Novartis and Bluebird need to go for these virtually unprecedented prices in order to make their therapies profitable.

This is informed by the experience of CAR-T cell therapies, where Novartis’ Kymriah – the first ever CAR-T approved in 2017 – looks set to remain a loss-leader for many years. Kymriah’s US list price is $475,000 while Gilead’s rival drug, Yescarta, is priced at $373,000 (with European prices substantially lower than this).

Meanwhile, Spark Therapeutics’ Luxturna for a hereditary eye disease (marketed by Novartis in Europe) costs around $425,000 per eye, bringing it close to that $1m mark.

Bluebird is also unusual in that it is launching this groundbreaking product in Europe first, ahead of the US.

Several factors inform this: the flexibility of the EMA’s PRIME fast-track for cutting-edge therapies, the higher numbers of beta thalassemia patients in Europe compared to the US, and Europe’s single- payer healthcare systems. The simplicity of talking to one payer in each country, Bluebird hopes, will help it negotiate its novel risk-sharing outcomes- based deal more easily than in the States.

Innovating in outcomes deals in Europe

Leading these conversations in Europe is Andrew Obenshain (below), the company’s head of European operations since 2016.

He’s seen a rapid change in attitudes towards healthcare systems in the last 12 months, as awareness of cell and gene therapy grows.

“Compared even to just a year or two years ago, the openness to these types of conversations is much greater. Governments can see this coming and they’re looking for solutions,” he said.

Bluebird is focusing on Germany, Italy, France and the UK as its initial launch markets, as 90% of Europe’s beta thalassemia patients live in these four countries.

However, patients from other European nations will also be able to travel to the treatment centres, of which there will be two or three in each of these countries. Bluebird has invested heavily in health economic expertise internally, and has built its own outcomes models to predict how much the treatment could be worth in real terms.

Much of this pricing is based on direct comparisons with the costs of lifelong blood transfusions and haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation. The latter cost anywhere between $500,000 and $1m, while also carrying the risk of having to treat adverse events such as graft versus host disease, for example.

The firm’s modelling has focused on four areas of value: the improved quality of life, the extended life years, the costs defrayed from the health system and then the wider societal benefits.

The company’s models arrived at a value of $3-4m when all these were factored in, however Obenshain said it is disregarding defrayed costs and the societal benefit “because those are what the governments can use to pay for our therapy”.

Instead the firm arrived at a maximum value of $2.1m – not a price but a ‘ceiling value’, however, as indicated already, the eventual price (as yet undisclosed) is likely to be closer to $1m.

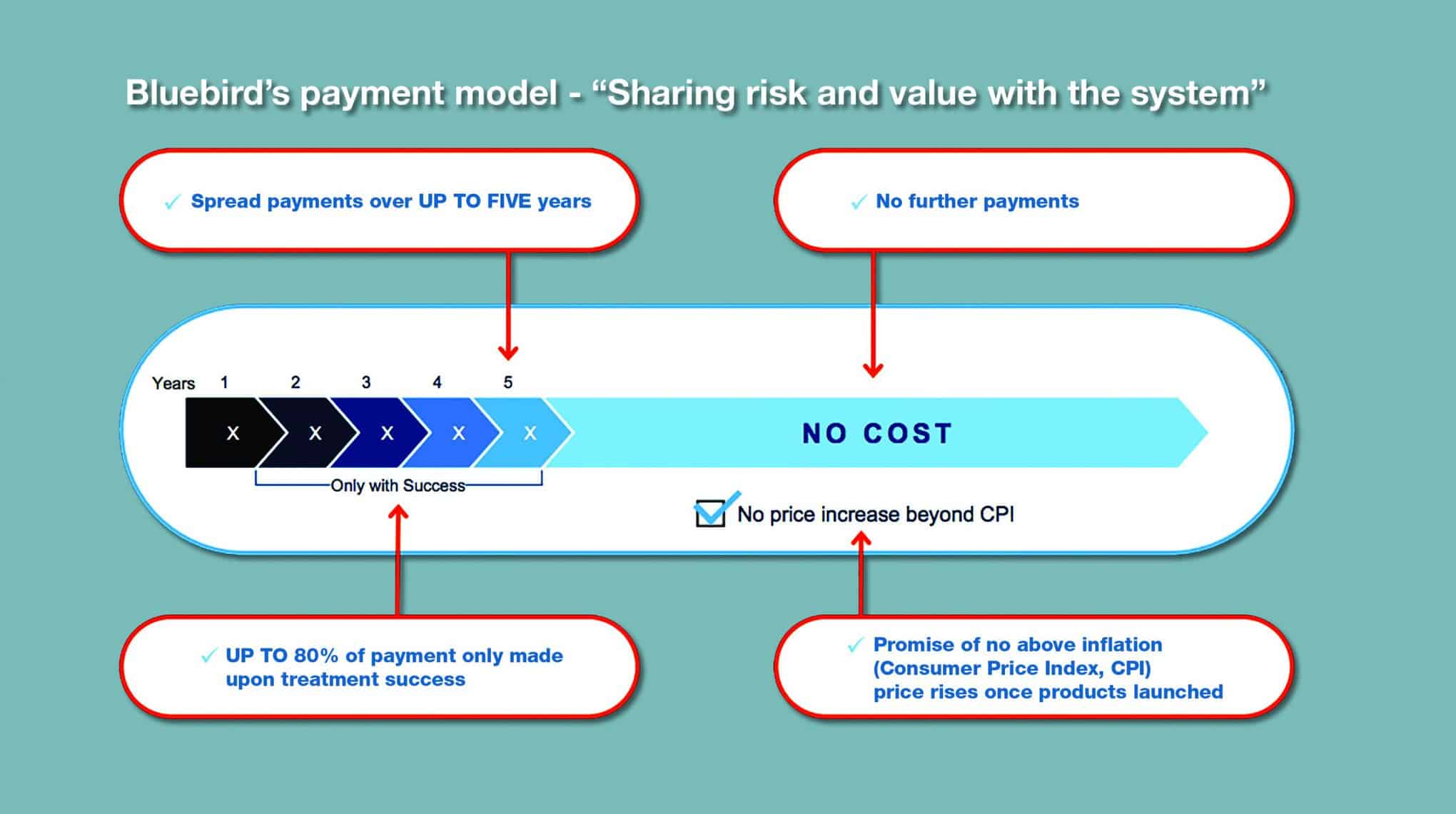

Bluebird’s approach is attractively simple: the cost is spread out over five equal instalments of 20% over five years. The key is that only the first payment is non-negotiable – all the others will depend on the response of the patients.

“We’re saying that instalments two, three, four and five only get paid if the product is successful,” explained Obenshain.

“The most obvious endpoint for that success is transfusion independence, as that’s how we measure our trials. Since we unveiled that approach in January we’ve been starting to engage with whoever wants to engage and discuss this model, conceptually.”

Among these markets, Italy looks set to be particularly significant for Bluebird and Zynteglo based on two factors: the country has been a leader in outcomes-based agreements with industry, and is also home to Europe’s biggest population of beta thalassemia patients.

“All the European countries are testing grounds for us, but particularly in Italy,” said Obenshain. “There is quite a patient population there, about 6,500 people [with beta thalassemia], so that’s a country we are very focused on and will be in active dialogue with.”

Obenshain made it clear that the company is looking to lay the foundations for a long-term solution, which will pave the way for more cell and gene therapies in its pipeline.

This incudes Lenti-D, a gene therapy for patients with cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (CALD), a rare, serious and life-threatening hereditary neurological disorder.

Its most important pipeline candidate, however, is the multiple myeloma targeting CAR-T therapy bb2121, being co-developed with Celgene. It’s tipped to hit peak sales of $5bn and is therefore most crucial to Bluebird’s future. This is less of a concern for Obenshain and his growing Bluebird team, however, as Celgene (shortly to merge with BMS) will oversee the commercialisation of the drug in Europe.

Netflix and other models

For its part, Novartis has tried to open up the conversation around novel payment methods, including looking at how other industries use financing to spread cost and share risk.

Novartis CEO Vas Narasimhan has suggested adopting a model using reinsurance, or finance deals commonly used by consumers buying cars. The huge global success of Netflix has also made it a reference point, with health payers in the US and Australia recently signing ‘subscription’ arrangements to finance expanded spending on hepatitis C drugs.

“We haven’t looked at external models so much,” said Obenshain. “Instead we’ve looked at the existing market and talked to people in those markets to help us determine what that should be.”

He said conversations with Germany’s sick funds have been constructive so far, not least because these insurers are used to working on similar outcomes- focused contracts, and are willing to engage.

If everything goes according to plan, most patients with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) treated with the gene therapy will stay transfusion-free for the rest of their lives, and won’t need the high-cost allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation which is currently the standard of care for the most acute sufferers.

Trials show that for a number of reasons, not all patients respond to Zynteglo, but these look likely to remain in the minority. Results from Bluebird’s phase 3 Northstar-2 study showed that, after more than three months follow-up, 10 out of 11 patients with non-β0/β0 genotypes have stopped chronic transfusions.

The positive CHMP opinion is supported by data from the phase 1/2 HGB-205 study, the completed phase 1/2 Northstar (HGB-204) study, data from ongoing phase 3 Northstar-2 (HGB-207), Northstar-3 (HGB-212) studies and long-term follow-up study LTF-303.

Bluebird is also expanding trials into more difficult to treat subtypes, including children and patients with the most severe β-thalassemia, so- called β0/β0 genotype. It is also investigating the therapy in sickle cell disease, with a phase 3 trial set to begin this year.

Analysts William Blair estimated last year that Zynteglo global revenues could exceed $800m in TDT, but this will depend on whether data shows it can provide curative treatment in the harder-to- treat sub-groups. Increasingly factored into this equation is competition from companies following Bluebird into beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease. These include pipeline gene-editing therapies from Sanofi and luspatercept from Celgene to name but a few, although Bluebird could have a decisive head start.

A target for big pharma M&A?

The imminent launch of Zynteglo will also increase speculation about a possible M&A move for the company from a major biopharma company. Fellow US gene therapy company Spark was acquired by Roche for $4.3bn in February as part of a wave of deals in recent months, while pre-market gene therapy company Nightstar was bought by Biogen for $800m in March.

Obenshain insisted, however, that Bluebird is investing for a long-term independent future, with its sights also set on taking Zynteglo into the Middle East and Asia, where beta thalassemia patients are far more prevalent.

These M&A moves confirm that gene therapy will be key to biopharma’s future – but it’s not clear just how far it will transform from being a manufacturer of pills and injections and long term medicines usage to one which oversees one- time therapies via a supply chain integrated with healthcare systems and sharing risks with payers.

A lot will depend on just how many diseases prove themselves targetable to cures through these methods, and how many prove resistant. However, those companies which prove themselves adept at fine-tuning their advanced therapies around durable patient outcomes and proactively building value-based systems with healthcare payers will reap the rewards and disrupt the existing business models of many of their competitors.