Your brand team is only as good as its people and your people are only as good as their behaviour. Wouldn’t it be good, then, to understand which behaviours differentiate effective and ineffective brand teams? And better still to know how to change those behaviours? This is a subject I teach and research, and my work finds six key differences between ‘nice’ and ‘naughty’ teams in life sciences companies. In this article, I explain those distinctions, how they influence team effectiveness and what we can do to mend the ways of badly-behaving teams.

Loose vs precise language

In most areas of the life sciences, our use of language is necessarily precise. Our scientists would never confuse a peptide with a protein. Our statisticians would never use the word ‘average’ if it risked confusion between mean, mode and median. Our finance colleagues are punctilious in defining profit and return in several distinct ways. But, in marketing, strategy, objectives and tactics are often used as synonyms. Similarly, the discrete, precise meanings of data, information, knowledge and insight are habitually ignored and the words are used interchangeably. In brand teams, fundamental terms like market segment or positioning are frequently used with no regard for their tight, technical meaning.

Loose language is the first and perhaps most pervasive bad behaviour that reduces the effectiveness of brand teams. It means that, however much we talk and share, we never communicate as well as we should.

Satisficing vs satisfying

These two similar words have very different meanings and describe behaviours with very dissimilar outcomes. Satisfying comes from the Latin ‘to content’. In a brand team context, it means fully delivering on an objective, such as submission of a market analysis or brand plan, in good time. Satisficing, however, means to meet only the minimum needs. Brand team examples of satisficing include presenting data in new formats but without providing the new insight that was hoped for. Or ‘ticking the boxes’ of a strategic plan template without identifying how it will create value or for whom.

Satisficing is an especially pernicious habit because it hides behind the apparent delivery of goals. But it replaces truly value-adding activity with simply moving work from desk to desk.

Compromise vs consensus

This is another pair of words that are often confused but which describe entirely different processes and outcomes. Compromise is the point at which a team settles after everyone has conceded some of their ideas. A consensus is an agreement built from synthesising those thoughts. In a brand team, decisions that require medical, marketing and access knowledge, such as value proposition design, can be compromise or consensus. Compromise propositions are the limited overlap between what we are willing to accept, often limited to indications, pricing and claims. Consensus propositions blend the three perspectives into something offering direct and indirect value to patient, payer and prescriber through product, service and intangible benefits.

Compromise has an undeserved good name because it is synonymous with avoiding conflict. But it destroys the value inherent in a team with diverse views and knowledge.

Fads vs fundamentals

Innovative industries like the life sciences thrive on new ideas and brand teams are especially open to the latest buzzword. But not every new idea has value and valueless fads can often drive out precious fundamentals. Brand teams who rely on external agencies and consultants are the most susceptible to this. Fads such as patient-centricity or omnichannel marketing contain a grain of self-evident truth, but that grain is wrapped in layers of hype and overpromise. Worse, fads divert both resources and attention from time-honoured fundamentals, like understanding market heterogeneity and leveraging your firm’s distinctive strengths.

Fads are sugar for brand teams. They are tempting and habit-forming, especially to young, less-experienced marketers. But, like sugar, when they displace the essential nutrients of good marketing, they are a bad habit.

Skimming vs science

Most activities in a life sciences company are rigorous and disciplined. There are tightly specified ways of doing everything from running a trial, to validating a manufacturing process, to submitting a regulatory dossier. By contrast, the techniques of marketing are often ‘skimmed’ – done in a superficial way without any real reference to their scientific origins and fundamental premises. The prime example of this in a brand team is SWOT alignment. The SWOT is used incorrectly, at the wrong time and with the wrong inputs, even though the science behind it has been understood for decades. In more effective teams, this contrasts with the scientific application of marketing techniques that have been standardised and built on a deep understanding of their principles.

Skimming has all the characteristics of a bad habit. It appeals to our human weaknesses and makes our life easier. But like any bad habit, its consequences find us out in the form of weak, poorly executed brand plans.

Conflict vs cooperation

The very essence of organisational effectiveness is the coordination of separate, expert functions such as marketing, medical affairs and market access. Cooperation across functional barriers is accorded almost sacred status in most firms. But much of what is called cooperation is disguised, implicit conflict.

In a brand team context, we see this as the setting of competing functional goals, competition for resources, implied blame, the control of information and politicised alliance building. The rare exceptions to this behaviour involve having aligned goals, demarcated resources, transparent information and apolitical commitment to the organisation, not to a function.

The habit of conflict flows from human traits such as self-interest, tribalism and social competition; it is the default position unless deliberate steps are taken to avoid it. But it leads to competitive energies being diverted inwards, away from competitors towards colleagues.

Causes and cures

Behavioural change in individuals is so difficult that it is almost oxymoronic. Every one of us has bad habits that have withstood years of attempts at change. This difficulty is amplified in an organisation, because it involves changing collective, interrelated and self-reinforcing behaviour, much of which is taken for granted.

There are, of course, thousands of books that claim to have uniquely effective prescriptions

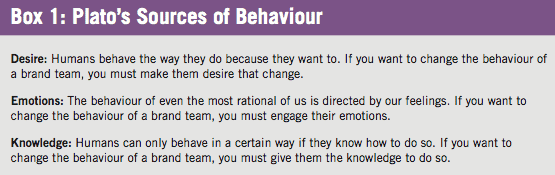

for changing the behaviour of organisations and groups. But reading these books carefully shows that they are all derived from a common, ancient source: the Greek philosopher Plato. The Platonic explanation of behaviour was that it flowed from three sources (see box 1).

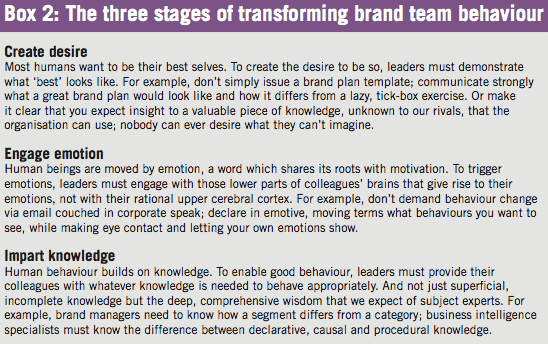

Plato’s triadic diagnosis leads, naturally, to a three-stage course of therapy. If you want to replace the bad habits of your brand teams with better, value-creating behaviours, then you must take three steps, which are as easy to say as they are hard to practice. These are shown in box 2.

What we repeatedly do

My research into what separates good and bad brand teams is, like any good research, complex and can seem somewhat abstract. But it is also, at a fundamental level, simple and practical. In the end, the brand team that produces good results is the one with the best people. And when we say the best people, we mean the people who have chosen to displace these six bad habits with the six, more virtuous behaviours described in this article.

Plato understood, long before anyone else, the three sources of these good behaviours, shown in box 1, and the way to achieve lasting behavioural change, as shown in box 2. But it was his pupil Aristotle who best summarised his teacher’s work. Paraphrased into modern English by the philosopher Will Durrant, Aristotle said:

‘We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.’ This is a lesson that every brand team leader, member and senior executive should learn.