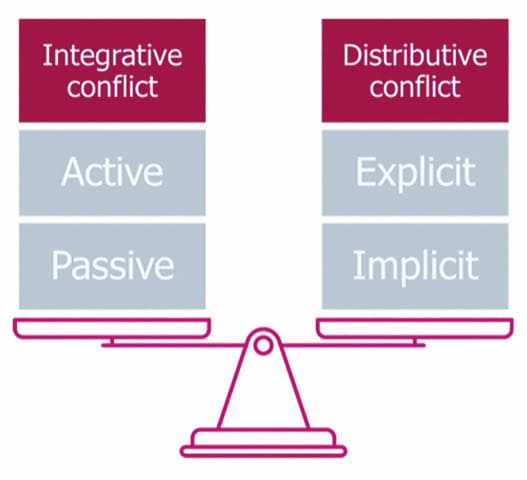

Figure 1: Types of cross-functional conflict

A distinctive feature of our industry is the enormous variety of capabilities that must be combined to develop and execute a strategy. More than almost any other industry, bringing a new medicine or medical technology to market and making it commercially successful needs a menagerie of functional skills.

From marketing to medical affairs, from market access to regulatory, from sales to government affairs, commercialisation in our industry is not just a team game, it needs teams of many diverse talents. Consequently, all effective firms place a premium on cross-functional working and alignment between functions. That why it’s been central to my research agenda for more than 20 years. This article is about what I’ve found, what I’ve understood and what it implies for improving cross-functional working.

Good conflict, bad conflict

My first important finding was surprising to many. There is such a thing as good cross-functional conflict. Called ‘integrative conflict’ in the jargon, it can be active or passive. The former is when your thinking is questioned constructively, and the latter is when challenges force you to raise your game. In both cases, integrative conflict is open and positive. By contrast, ‘distributive conflict’ is the name academics give the bad kind of intraorganisational conflict and it can be explicit or implicit. When it’s explicit, distributive is in interdepartmental bargaining, withholding key resources and creating unnecessarily high evidence and compliance barriers before agreeing to help. More insidiously, distributive conflict is commonly implicit. In this case, its methods include subtly deprioritising requests for help, withholding information and framing issues to deliberately undermine colleagues’ reputation. This implicit behaviour tends to be more harmful because, unlike its explicit counterpart, it’s harder to find and fix. As figure 1 implies, all of these kinds of conflict pervade all organisations. Leaders can’t eradicate it but they can tip the balance toward good conflict.

Tipping the balance

I often compare my research to that of an anthropologist who lives with a remote tribe to observe its culture. It’s fascinating but the answers aren’t obvious. They emerge from intensive observation and relentless questioning, which is built on a foundation of prior work in organisational psychology.

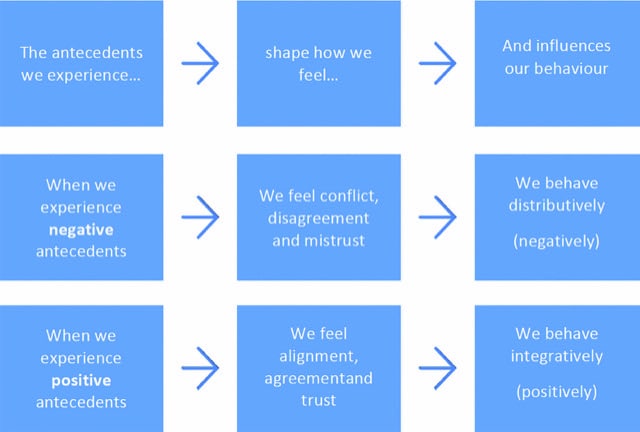

The psychologists tell us that our behaviour is boundedly rational. That is, it’s rational within the context as we perceive it and the situation as we experience it. What we perceive and experience shapes our feelings and our feelings influence our behaviour. When I used this ‘bounded rationality’ model as way of looking at cross-functional behaviour in pharma and medtech companies, what I found was a cause and effect pattern, as summarised in figure 2. Note here that the model uses the word ‘antecedents’, a word academics are fond of to describe something that precedes whatever they are studying.

Figure 2: Experience, feelings and cross-functional conflict

At first sight, this model may not appear very insightful. After all, it simply says that negative experiences cause bad conflict and vice versa. This doesn’t look like a breakthrough. But the value of the model was that it focused later research on to those antecedents. What tangible things, I wondered, have shaped colleagues’ feelings and tipped the balance of cross-functional conflict one way or another?

Casus belli, casus pax

The next phase of my research was, in academic speak, a comparative research question. What is different in firms with strongly positive, integrative conflict compared to their negatively, distributively conflicting peers? Or, in the words of one of my classically educated research respondents, what were the casus belli and casus pax (causes of peace or war)? To uncover this took a lot of time talking to life sciences industry executives, the equivalent to watching tribal rituals in a jungle clearing. It was the sort of research that social science researchers like me are trained for and vastly different from the hard, natural sciences training I had received when I was a chemist at the bench. But my training paid off and, eventually, a clear picture emerged. This resolved into a set of seven factors that tended to precede positive, integrative cross-functional behaviour and another seven antecedents of its antithesis of negative, distributive conflict. These are summarised in figure 3.

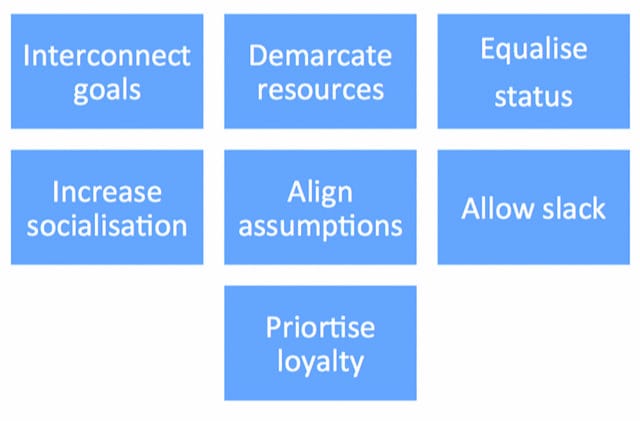

Figure 3: The antecedents of positive and negative conflict

These findings allow us to paint a word picture of an organisation that tilts towards good cross- functional working, characterised by both active and passive positive, integrative conflict. In this company, the goals of different departments would reinforce each other and not conflict. Each department would own its resources and would see itself as respected by other departments. Physical proximity – sharing coffee rooms and offices – also helps, as does sharing assumptions about what is important to the success of the business. In our exemplary company, all of these factors would be amplified by something academics call, rather arcanely, organisational salience. This simply means that individuals feel loyalty to the company. Finally, good cross-functional working is helped by ‘organisational slack’, some free time for colleagues to listen and talk to each other.

This model of cross-functional excellence is more informative if it is compared with the pen-portrait of its converse, an organisation that is likely to have bad cross-functional working, characterised by explicit and implicit negative, distributive conflict. In this model of what companies look to avoid, different departments would be set goals that had the potential to conflict with each other, such as sales and profit or speed to market and quantity of evidence. In the sort of company we never wish to emulate, departments are forced to fight for shared resources, such as shared sales teams.

There is also a status hierarchy between departments, which encourages lower-status functions to undermine those who are in the ascendancy. These issues are amplified when colleagues work at a distance, in different buildings or countries. This leads to differing assumptions about what is important, for example between those who think clinical outcomes are paramount and those who think professional relationships are critical. The opposite of organisational salience is group salience, when primary loyalty is to a profession or department, not the company, and group salience worsens negative conflict. Finally, organisations where everyone is overstretched and under pressure are often those in which cross-functional working is least effective. Stress, or simply lack of time to talk and listen, leads to the feelings that cause distributive, negative conflict.

Cross-functional levers

Delighted as I was and am with these academic findings, and the suite of four peer-reviewed articles that flowed from them, I was even more excited about the practical application of my research in pharma and medtech companies. Amongst our industry’s leaders, cross-functional working is rightly seen as essential to effective strategy execution. It’s also seen, almost universally, as a problem. Even the best companies seem to wish their cross-functional working was better, so allowing strategy to be created, agreed and put into action faster and more effectually. The leaders I spoke to often expressed frustration because, for all its importance, cross-functional working seems fluffy, intangible and hard to manage. As one leader said to me, “I know I need to improve it, I just don’t know what levers to pull”. This shows what those seven levers are. First, set interdependent goals, so that no department can achieve its metrics unless the others do too. Second, demarcate resources, so they don’t create an excuse for turf wars. Third, treat departments equally, boost those seen as less important and encourage humility among those departments who lack it. Fourth, if you can, put people close together. If not, give them lots of time to socialise. Fifth, get departmental leaders to surface their beliefs about what is important to the business’s success and, if they disagree, guide them to agreement. Sixth, ruthlessly squash middle-managers who create cliques within the company. The company comes first, always. Finally, and most difficult of all, allow teams to work at less than 100%, at least some of the time. The free time may not be measurably productive but it is immeasurably useful for improving cross-functional working. These seven lessons are summarised in figure 4 and are deliberately not numbered because they are mutually synergistic.

Figure 4: Levers of cross-functional strategy execution

In short, alignment angst – the challenges all leaders face in executing strategy through cross- functional teams – is prevalent and significant in life sciences companies. But, with an understanding of its antecedents and mechanisms, it’s manageable by pulling these seven levers.