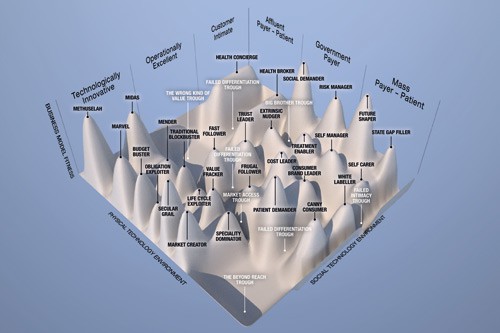

Figure 1

In the preceding two articles in this series, I described the forces shaping the life science industry (see Under Pressure, PME Feb 2016) and the subsequent emergence of 26 new business models (See Explosive Evolution, PME June 2016). This newly complex landscape, summarised in figure 1, means a plethora of choices for industry strategists and makes it all the more important that they choose their future business model carefully. But how, faced with such complexity, can we pick the model that will work best for us? My research into how firms answer this question reveals a four-step process for navigating the life science market of the future.

Step 1: From history to destiny

Although, in theory, firms can choose between any of the 26 business models shown in figure 1, in practice they are constrained by their history. A firm’s past leaves it with a culture and set of capabilities that are difficult, if not impossible, to transform. Some change is possible but the reality is that, for example, a research-based firm such as Roche or Merck will find it hard to become a cost-led model similar to, for example, Sun Pharma and vice-versa. This ‘path dependency’ effect means that most firms have a limited set of feasible options, usually in those parts of the landscape they are familiar with.

The first step for a firm choosing its future business model is therefore to identify the limited number of feasible models and then to reify them. By that, I mean to think through, in some detail, what each model would look like for the firm. This is essential because the detailed design of each model is context-specific. For instance, if Novo Nordisk designs a secular grail model by combining IBM’s Watson with its own therapies, it will be different from, for example, Novartis’ secular grail model combining immuno-oncology and companion diagnostics. And the detailed, context-specific design of possible future business models has to be envisaged before firms can rationally choose between them, as will become obvious in the next step.

The detailed, context-specific design of possible future business models has to be envisaged before firms can rationally choose between them

Step 2: Deciding how to decide

Given a limited, but still complex, set of feasible business model options from which to choose, it is all too easy and common to make a hurried, unsophisticated choice. In my research, I often observed firms choosing almost entirely on single, simple criteria such as market size. But the more thoughtful executives I interviewed described how they began by deciding on what basis they would choose between models. Examples of the criteria they used are shown in table 1, which also reveals that they considered not only the attractiveness of each model but also the probability that it could be successfully developed. Importantly, the best firms I spoke to developed criteria that were case-specific and based on the organisation’s appetite for both risk and return. In other words, they avoided ‘cookie cutter’ approaches to choosing between business models that are often pedalled by consultancies.

| Factor determining the attractiveness of a business model | Factors determining the risk of a business model |

| Volume size of market | Closeness of current new product development capabilities to those needed by new model |

| Profit pool available | Closeness of current operational capabilities to those needed by new model |

| Growth trends in volume | Closeness of current customer relationship management capabilities to those needed by new model |

| Growth trends in profit pool | Closeness of current organisation structure to that needed by the new model |

| Level of direct competitive intensity faced by this model | Closeness of current organisational culture to that needed by the new model |

| Internal synergy of this model with others (ie synergistic effects arising from interaction of resources within the firm | Closeness of the current network of alliances and relationships to that needed by the new model |

| External synergy of this model with others (ie synergistic effects arising from interaction between customers |

Closeness of current asset and resource scale to that needed by the new model |

Table 1: Factors determining business model choice

Step 3: Relative ranking

Given a reified set of business model options and a set of assessment criteria tailored to the firm’s goals, executives were now able to compare business models more deliberately. This involves determining the attractiveness of each model by assessing, weighting and combining the multiple attractiveness criteria they had identified in step 2.

A similar process for determining the risk associated with each model, again using multiple, weighted criteria, accompanies this. This laborious but necessary process translates the list of alternative business models into two lists: one ranking the models in terms of their attractiveness, the other in terms of the risk associated with building this model. An important, practical lesson that emerged from this part of the research was that almost all new business models under consideration can be viewed as both attractive and risky, making it hard to choose between them. To allow for this, firms ranked alternative models in relative, not absolute, terms. The output of step 3 was therefore a relative ranking of each possible new business model’s attractiveness and riskiness. As I observed this, I could see that this stage of the process was conceptually similar, but technically different, from techniques that have long been used to manage portfolios of products, countries and other business units.

Almost all new business models under consideration can be viewed as both attractive and risky, making it hard to choose between them

Step 4: Placing bets

The outputs of step 3, which of course depend on the outputs of steps 1 and 2, allow executives to condense a very large amount of information into a relatively simple picture. The details of the reified alternative business models and the multiple factors that determine their attractiveness and risk can be condensed into a table such as that shown, in simplified form, in table 2, with each box containing one or more contending business model.

The value of this portfolio approach to assessing business models is that it gives a much more nuanced guide to executive action than the simple yes/no, binary outputs of other, simpler approaches. Even at its simplest, it makes one of four recommendations for how to proceed with a potential new business model:

- Focus: Business models that are relatively attractive and low risk deserve all the resources they require. Typically, these models are significant but viable developments of existing models that use mostly extant capabilities to exploit new opportunities.

- Build: Business models that are relatively attractive and high risk justify only the resources necessary to build them while mitigating risk. Typically, these models are radical departures from current models in order to exploit new opportunities.

- Manage: Business models that are relatively unattractive and low risk justify only the limited resources necessary to maintain a positive cash flow. Typically, these are existing business models that require extant capabilities in order to exploit existing, mature opportunities.

- Avoid: Business models that combine relative unattractiveness with high risk do not justify any significant resources and may provide an opportunity from which to divert resources to other models. Typically, these models are radical departures from extant capabilities in order to exploit existing, mature opportunities.

| Low relative attractiveness | High relative attractiveness | |

| High relative risk | Avoid or withdraw | Build |

| Low relative risk | Manage | Focus |

Table 2: A portfolio comparison of business models

Pick few, pick wisely

In this article, I have described the practice I observe when firms try to answer the most fundamental question about their future: Which business model shall we attempt to develop? The importance of this question means that it must be answered with great care and careful process. Often, care is mistakenly conflated with volume of data and size of spreadsheets but effective firms follow the four-stage process I have described. For all its stage-by-stage simplicity, this process is as much judgement as analysis and as much craft as science. The answers that result from this process are always clear but often nuanced. Most of all, the value of this approach in choosing which model to build lies as much in the executive discussion it enables as in the answer it provides. And of course even that answer only creates more questions about exactly how to build the structures, strategies and capabilities of the new business model. I will address those questions in the fourth and final article of this series.