The ultimate aim of a key account team is to meet customer needs more effectively while reducing cost of service. This move has been prompted by increasing detailing costs, currently in the order of £150 to £200 per call, declining duration of detail and sharply declining access.

The original key account model is generally credited to Procter & Gamble (P&G), a company that moved on from a product category structure where each customer received multiple calls from different P&G sales forces. This situation is analogous to many pharma companies, where sales forces are frequently structured within a pod system, with several sales teams strategically overlapping to work with the same doctor, with multiple representatives. The aim is to increase share of voice, maximise physician response to detailing and, in theory, improve customer relationships.

The aim of P&G’s change was to separate major customers and develop a partnership between purchaser and manufacturer. This targeted approach focused on increasing efficiency, improving service levels and reducing sales force costs. As a model it has much to commend it but why has it not realised its true potential within pharma?

There are of course a number of salient differences between the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market and that pertaining to pharmaceuticals. In contrast with FMCG we rarely sell directly to the customer but through a gatekeeper who prescribes on behalf of the end users. Secondly, the prescribing freedom of doctors has generally been eroded as guidelines and formularies restrict choices or guide prescriptions. These factors aside, if key accounts are indeed likely to bring about the aforementioned benefits a number of important changes have to be adopted.

Waste not

In most sales forces it is recognised that between 30-40% of activities are wasted. This is a combination of several factors. Strategic drift occurs when we fail to align our promotional activities with our market. The mechanism that causes this is the common practice of using last year’s budget as the template for this year’s plan. Good practice is to measure the ROI of each activity at the end of each promotional period and adjust our budget in accordance with the results. A second major cause of waste is too much time spent on customers who have little or no impact on sales. Such cost sinks are a major cause of promotional waste. A major issue with key accounts is ensuring that activities chosen reflect local, not necessarily national, needs and are restricted to customers who significantly influence or drive demand.

Activities need to focus on customers who significantly influence or drive demand

It is also important to understand the promotional mechanism that drives sales and builds market share. Here a common issue is that, unlike the P&G model outlined earlier, the key account manager does not have sole responsibility for the account but merely adds another element to the sales force pod structure. Under this scenario the risk of conflicting messages is high, which can lead to a confounding effect on sales rather than the delivery of a crisp value proposition. A further weakness is the risk of excess calls being delivered, resulting in more promotional waste, lower coverage and loss of opportunity.

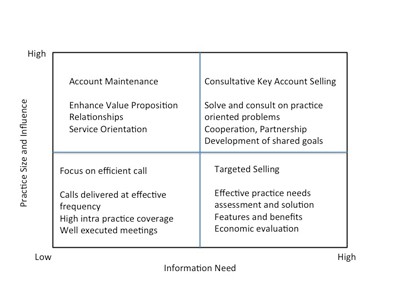

Figure 1:

Key accounts should therefore be designated as such and chosen on the basis of market potential, influence and need for information. Figure 1 demonstrates this classification, where key account customers should fall solely within the top right quadrant of this customer matrix.

A common mistake is to use absolute sales as a measure of potential. The aim of key account managers should be to develop a partnership approach with their customers where, through using their knowledge and consultative skills, the company’s products can be optimally positioned. A further aim is to develop advocates who will positively influence their network, resulting in the optimal use of guidelines and current practice to render the prescribing environment more receptive to promotion. Some companies have started to work along these lines, but they are few and far between.

Such long-term goals are not accomplished overnight but require careful planning and persuasive argument. Delineating key accounts solely on the basis of absolute sales may therefore be misleading. If you do Pareto twice, 4% of activities equates to 64% of sales. A rule more in line with 10/75 should perhaps be applied in terms of key accounts, where influence may considerably outweigh sales potential.

Figure 2:

It is also important to understand how practices and hospital departments adopt new products. If we define an innovation as the commercialisation of an idea then influencing the adoption process is the key to success. Common practice is to target customers either on their potential or on past relationships, neither of which may be a good indicator of propensity to adopt. Recent research at Aston University produced a very accurate predictive model that allows us to accurately position GP practices or hospital departments on Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation curve (see figure 2).

Managers should develop a partnership approach with their customers

Clearly concentrating targeting efforts on practices or departments located at the left-hand side of the curve is far more likely to yield productive results. This research reveals that new products are evaluated against each physician’s ‘evoked set’ – the group of products that the physican is familiar with and routinely uses. This evoked set varies in breadth depending upon therapy area and is built from experience over time. Knowledge of this set is also critical to position your new product successfully. Each product is evaluated in terms of its characteristics and perceived merits with emphasis on which product its use would replace. This latter argument is particularly important when positioning the product with payers and those who influence position on guidelines. Use of this prescribing continuum proved successful in assisting companies to successfully target and launch new products, where the probability of a practice adopting a new product can be very accurately determined. Focusing detailing efforts upon these receptive practices or departments is far more likely to result in subsequent trial and adoption.

Once an individual physician has adopted a new product it spreads by means of contagion. This is a factor of the breadth of influence of the doctors, which is dependent upon their relative position and the breadth and depth of their network. As a general rule intra-practice contagion is faster within larger, urban, more organised practices aided by mechanisms such as practice case review, rotation of authorisation of repeat prescriptions and attendance at local CME events. Good practice in key accounts is having knowledge of nodes of influence within their customer network where judicious choice of meetings and selective conversations can greatly enhance the speed of uptake and accurate positioning of new products.

Brand building is however best measured by adherence where a practice or department demonstrates steady and persistent use in contrast to occasional, sporadic or intermittent use. The propensity of practices or hospital departments to develop an adherent habit can also be accurately mapped along Roger’s diffusion curve and is a useful tool to ensure a strong upward sales trajectory. This is a far more reliable and predictive measure of future product success than monthly sales or the number of new practices using the product.

Effective account management

Effective key accounts are therefore dependent upon clear delineation of tasks, where the key accounts manager (KAM) adopts primary responsibility across a range of products with the freedom to negotiate within clear guidelines. Productive marketing uses the KAM’s local knowledge to ensure that the choice of activities and the chosen customer focus is based upon local opportunity not national dictate. How key accounts are chosen and treated separately from other customer segments is a critical decision within this planning process.

Effective decisions are however data driven and it is critical to understand which activities actually work and how the local environment operates. Good KAMs know more about their account status than the customers do. Each account should be managed as an effective profit and loss account with an aim of maximising lifetime value, not just short-term returns. Reports produced should mirror, support and drive this process. Key accounts are different and should be treated as such.