The oft quoted Art of War states: ‘Know your enemy; know yourself; and in 100 battles you will not be in peril.’ Marketing can often be described as a form of warfare where the profits accrue to the victors and the losses to the losers. Here the best source of profits is growth.

Despite these assertions we cannot often choose our products, or indeed which market to compete in. We can however ensure that we know our market – our terrain in military terms – better than our competitors and use that knowledge to our advantage.

Prior to 2010 those seeking to understand GP in the UK and sales behaviour had little alternative but to use IMS data or some form of primary data collection in order to understand GP attitudes to their products. After July 2010 the UK government began to release GP prescribing data at practice level. For the first time we could see where sales originated from, without the vagaries of apportionment and what precisely single-handed GPs were prescribing. At approximately 10 million rows a month this is an extremely detailed data set that provides myriad opportunities for marketing.

When examining the GP prescribing data for the last year and comparing it against the previous year, little growth is apparent. In fact on average the GP market is down just over 1% on the previous year. When examining the broad therapeutic categories, only 2 of the 16 within the BNF show any sign of growth – one of which is section 6 – endocrine.

This broad category has seen considerable activity in the last decade driven by two successive class introductions – the DPP4s and SGLT2s; both licensed for type II diabetes. These provide an interesting example to illustrate some of the many uses of the richly detailed prescribing data.

The first step is to define our market. This is not always as simple as it seems since companies, even those operating in the same space, often define their market differently. Here it is important to distinguish between competitors and complements and bystanders. Competitors actively compete for the same patients, which means that to grow in a sluggish market you have to actively displace the rival product – to grow at its expense. Complements are products that are often used together. Sometimes this distinction becomes blurred, as with metformin, which is a treatment for type II diabetes in its own right and also used in combination with a DPP4 or an SGLT2. The aim is to include all of your direct competitors that can conceivably affect your share of the defined market.

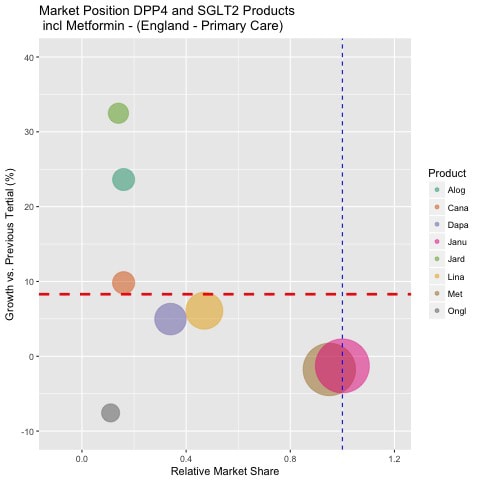

Having defined our market, next we should calculate the relative market share of the products. This consists of the market share of each individual product divided by the market share of the largest competitor, where a ratio of 1 denotes the market leader. The advantages of relative share is that it shows competitive strength and is a leading indicator of profitability. Many products are launched that never actually repay their development or promotional costs, and examining the relative shares of products is a convenient way to mark where profits are accruing within your market.

Figure 1 (pictured right) shows the position of the DPP4/SGLT2 market for the last four months to March 2017 in English GP practices compared to the previous Tertial (four months). The size of the circles denotes current sales, while reading the x-axis provides the relative market share figure. The dotted horizontal line denotes market growth. The vertical dotted line indicates market leadership where Sitagliptin (Januvia) is the clear winner that is no longer growing at the speed of the market. The large product beside Januvia is metformin that, although slightly less in cash terms, is a generic product which in real terms commands a great many more prescriptions. This points out the need to compare prescription numbers in a similar graph when comparing products.

Figure 1 (pictured right) shows the position of the DPP4/SGLT2 market for the last four months to March 2017 in English GP practices compared to the previous Tertial (four months). The size of the circles denotes current sales, while reading the x-axis provides the relative market share figure. The dotted horizontal line denotes market growth. The vertical dotted line indicates market leadership where Sitagliptin (Januvia) is the clear winner that is no longer growing at the speed of the market. The large product beside Januvia is metformin that, although slightly less in cash terms, is a generic product which in real terms commands a great many more prescriptions. This points out the need to compare prescription numbers in a similar graph when comparing products.

Notable points are that despite the considerable promotion and, some would say, superior clinical data, none of the SGLT2s has exceeded Trajenta (linagliptin) – a 4th entrant DPP4 in sales. Secondly, growth is ebbing away from Forxiga (dapagliflozin), the first entrant of the DPP4s, which is actually growing slightly slower than Trajenta. The remaining two SGLT2s are growing faster than the market, with Jardiance (empagliflozin) leading the market in terms of growth. Perhaps the surprise of the market is the growth of Vipidia (alogliptin) – a late 5th entrant DPP4.

This graph raises interesting questions regarding the strategy behind these different brands and it is important to note that if we draw the same graph using data from Northern Ireland, Scotland or Wales we will get a different picture. This reflects the fact that promotion is context specific and that the various countries within the United Kingdom behave differently – perhaps starkly illustrated by the Brexit vote!

Combining the GP prescribing data with other sources also allows us to build profiles of the type of practices prescribing our products and their salient characteristics. Such information can be extremely valuable in targeting.

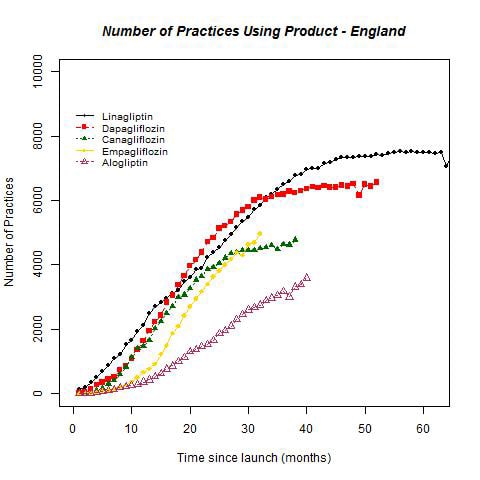

Figure 2 (pictured left) shows the launch trajectories of selected diabetes products and allows us to examine how well these products are doing in terms of practice recruitment. For ease of comparison this graph again depicts English practices and shows the practice penetration of each of the most recently launched products since launch. The x-axis shows time in months from launch and the y-axis shows practice recruitment.

Figure 2 (pictured left) shows the launch trajectories of selected diabetes products and allows us to examine how well these products are doing in terms of practice recruitment. For ease of comparison this graph again depicts English practices and shows the practice penetration of each of the most recently launched products since launch. The x-axis shows time in months from launch and the y-axis shows practice recruitment.

The key points here are that Trajenta is used by just under 8,000 practices but appears to have plateaued over a year ago. Forxiga and Invokana (canagliflozin) appear to be reaching a plateau but at different lower levels. In contrast Jardiance and Vipidia are still growing where Jardiance (the 3rd entrant SGLT2) appears to have overtaken Invokana (the 2nd entrant). This and the success of Vipidia appear to confound the ‘Rule of three’ put forward by Bruce Henderson – founder of the Boston Consulting Group. Henderson however was talking about profits accrued to the products in a market which is often markedly different from perceived market performance.

Questions raised by the second figure are which practices – dispensing vs non-dispensing and size for example – are most important for each brand? How does the practice pattern for each brand compare and where are the overlaps? The CCG to which they belong might also provide a further interesting perspective on this.

This allows us to understand the context within which our brands are being used and to tailor our marketing accordingly. We should not forget however that profit is the aim of the game, where use of relative market share to understand competitive position, both at the intra- and inter-practice level, can be extremely useful to understand both competitive dynamics and the most suitable tactics to deploy.

In conclusion marketing does not take place within a vacuum and if we understand the terrain within which we are operating we can wield our promotional instruments much more effectively. Unfortunately a lot of analytics appear to meet the needs of immediate reports rather than focus on the key questions of understanding the market and uncovering opportunities for competitive advantage. The NHS prescribing data offers a rich and valuable resource in this regard.